When England had a Spanish king – and what that tells us about Camilla's title

As the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla approaches, interest in the new queen’s title has grown – especially after the coronation invitations dropped the word “consort”, traditionally used to identify the spouse of a ruler.

Her title had already been widely discussed when the now king and queen married in 2005 (when Camilla chose to be known as Duchess of Cornwall instead of Princess of Wales). And it was also reported then that once Charles ascended the throne, she would be known as “princess consort”.

Considering the case of England’s forgotten Spanish king, Philip (who reigned from 1554 to 1558), husband to Queen Mary I, can help us rethink the word “consort”.

Philip II of Spain is usually associated, in the English-speaking world, with the defeat of the Armada in 1588 and the religious and military conflict between Elizabeth I’s Protestant England and Philip’s Catholic Spain. It is easy to forget that the man who sent his ships against Elizabeth – his former sister-in-law – had once been the king of England himself.

In lists of English kings and queens, he is usually omitted. The reason for this being that Philip is usually remembered and portrayed, both in popular imagery as well as in academic works, as a “king consort” and not a “king regnant”.

This view stems, partly, from a series of stratagems devised to curtail Philip’s power. The marriage treaty published in January 1554 presented some restrictions, even if it conferred the title of king on Philip. He could not dispose of offices of the realm freely and he could not bestow them on those who were not “natives”.

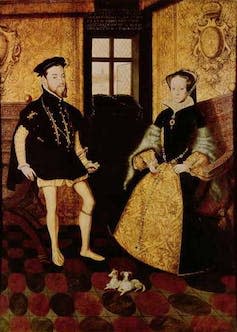

If the marriage remained childless, he would have to relinquish his kingly title when Mary died. After the marriage in Winchester on July 25 1554, Philip appeared in public events at the left side of Mary – the place traditionally reserved for the king’s queen consort – and he was made to sit on a lower chair. Also, it quickly became clear that parliament would not acquiesce to the king having a coronation.

However, none of this meant that he was a “king consort”. The early modern world was ruled according to strong patriarchal frameworks, and even though women could wield power in several European kingdoms, this was relatively rare and often considered undesirable.

Queens regnant (queens who exercise power in their own right) were proclaimed, therefore, when there were no viable male heirs. In fact, Mary was England’s first queen regnant and her father, Henry VIII, had gone to great lengths to prevent her from ever becoming so (unsuccessfully, as it turned out).

In the early modern world, therefore, the mere concept of a “king consort” did not exist – it was unthinkable. So it is not helpful to apply it to Philip.

When he married Mary, Philip was already a king – of Naples – and he ascended the Spanish throne in 1556, but he also acted as a full king of England. He appeared on coinage alongside Mary, he had a say on diplomatic appointments, he brokered England’s reconciliation with Roman Catholicism, and he created a new advisory board: the select council. In November 1554, he had even given the opening address to parliament and from then on always appeared on the right side of Mary.

Queen Camilla

The noun “consort” in this context means “a wife or husband, especially of a ruler”. In that respect, Camilla is a consort to King Charles as much as he is to her. When the word is appended to the noun “king” or “queen”, however, what it highlights is that he or she bears the title only through the right of their spouse. Yet, under common law, upon the accession of a king, his wife automatically becomes the queen.

The fact that the previous monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, was a queen regnant whose husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, was known as “prince consort”, created some confusion, which explains why Camilla has been officially referred to as the queen consort since Charles’s accession.

This was also the expressed wish of the late Queen Elizabeth in her Accession Day message of February 2022. This was in line with both tradition and legality, and it heralded the beginning of a transitional period designed to familiarise the public with Camilla’s status as queen once King Charles ascended the throne.

That the new queen will now be formally addressed as Queen Camilla does not mean that she will be gaining a new or different title, only that the potential confusion of the preceding months no longer holds. Although the word “consort” in the title is no longer deemed necessary, she will still be the queen consort of the UK.

King Philip’s case is different because his marriage was conceived as a shared rulership. Philip is often considered a forgotten monarch, but he behaved fully as king of England and in the gallery of royal portraits in the House of Lords, commissioned in the 1850s, he stands in the place that recognises him as such, between Mary I and Elizabeth I.

This piece is part of our coverage of King Charles III’s coronation. The first coronation of a British monarch since 1953 comes at a time of reckoning for the monarchy, the royal family and the Commonwealth.

For more royal analysis, revisit our coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum jubilee, and her death in September 2022.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gonzalo Velasco Berenguer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News