Found: World's Oldest Message in a Bottle, Part of 1914 Citizen-Science Experiment

A charming and fitting end to an experiment that began in 1914 with roots way back in the 1840s.

A Scottish fisherman has found the world's oldest message in a bottle, the Guinness Book of World Records confirmed last week. It is 98 years old, and was cast into the ocean by Captain C. Hunter Brown*, a scientist at the Glasgow School of Navigation, who was studying the currents in the North Sea.

AP

The bottle was one of 1,890 bottles released on June 10, 1914, and the 315th to be entered into Captain Brown's log, which is still kept and updated by Marine Scotland Science in Aberdeen.

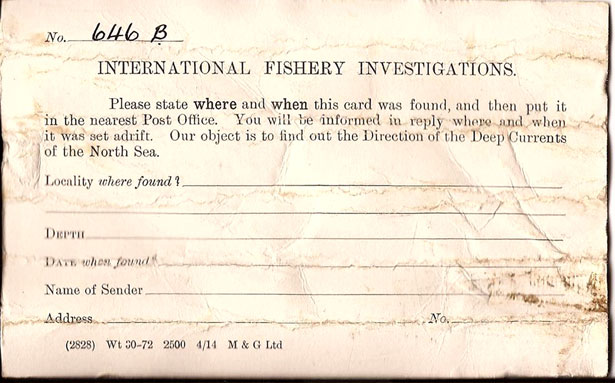

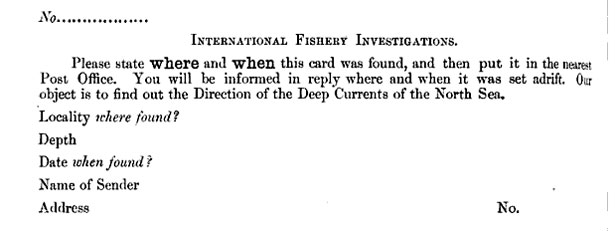

I'd say this qualifies as a nearly century-old citizen science experiment, though that's not a term scientists would have been familiar with then. Just take a look at the card contained in the bottle (which could be sent back to Hunter without postage). These drift bottles were data traps, intended to capture information with the help of regular people.

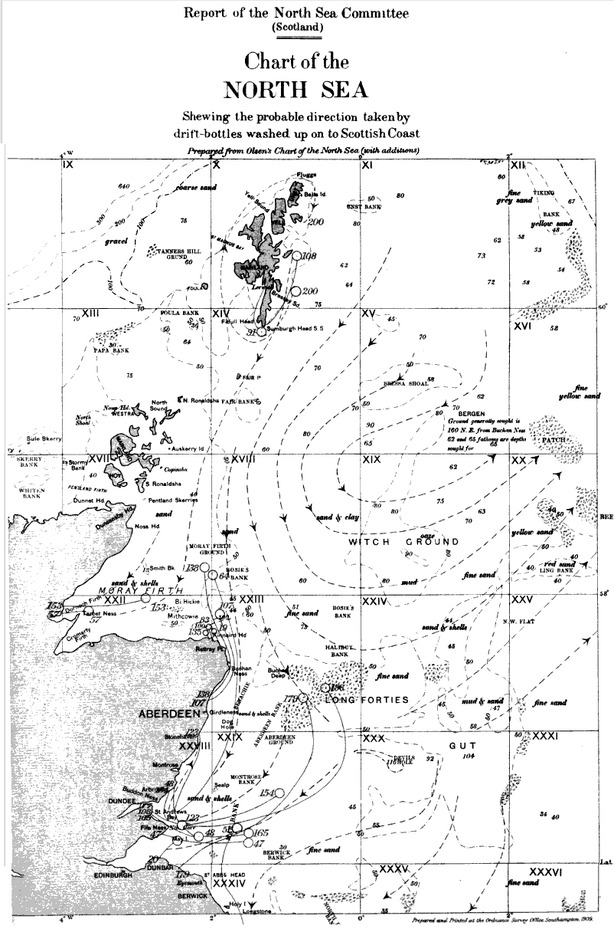

"Drift bottles gave oceanographers at the start of the last century important information that allowed them to create pictures of the patterns of water circulation in the seas around Scotland," explained Bill Turrell, Head of Marine Ecosystems with Marine Scotland Science explained in the official press release on the event. "These images were used to underpin further research -- such as determining the drift of herring larvae from spawning grounds, which helped scientists understand the life cycle of this key species."

But we don't have to take Turrell's word for it. Google scanned some old Scottish fisheries reports that contain reports from Brown's experiments. Sadly, copyright law prevents us from looking at the 1914 experiment, but we have full-text access to an earlier operation from 1907, which appears to have been the test case for the later, larger bottle drop. In fact, here's Brown's planned card, as shown in the 1907 version.

And we even have one of the charts of water circulation that he created with the data from his bottles.

Brownr's experiment was modeled on earlier surface current drift-bottle work by T. Wemyss Fulton, as well as similar studies by the United States Hydrographic Office. The entire field got its start when a British Navy office, Commander Becher, decided to use Nautical Magazine as a place to collect messages found in bottles by mariners across the world. They tracked 119 bottles this way, all of which you can see and plot in a Google Books scan. Altogether, the data Becher collected could be summarized thusly (by a magazine reporter a century ago):

Altogether, the uniformity in the direction of the courses of the bottles between the points of departure and arrival was found to be very remarkable, making all due allowance, of course, for some of the bottle voyages which were thought to be too capricious to render much scientific service, but which, in reality, were not capricious at all, and depended on physical causes not sufficiently well understood at that time.

The very first bottle researchers were content to see where floating bottles went. Later researchers including Fulton had weighted the bottle necks with lead such that they floated *just* beneath the surface to avoid wind interference.

It's fair to say that Brown would not have considered that the "course of time" might run to nearly a hundred years.The present experiments were conducted by a special drift bottle, the device of Mr. G. P. Bidder. This is a bottle so weighted as just to float in sea-water; a long copper wire is then attached to it by which it is caused to sink, but as soon as the wire trails upon the bottom the bottle tends to float again. Accordingly it remains floating a few inches above the sea bottom, is carried along by the bottom current, and in the course of time may be scooped up by a trawl net or found stranded on a beach.

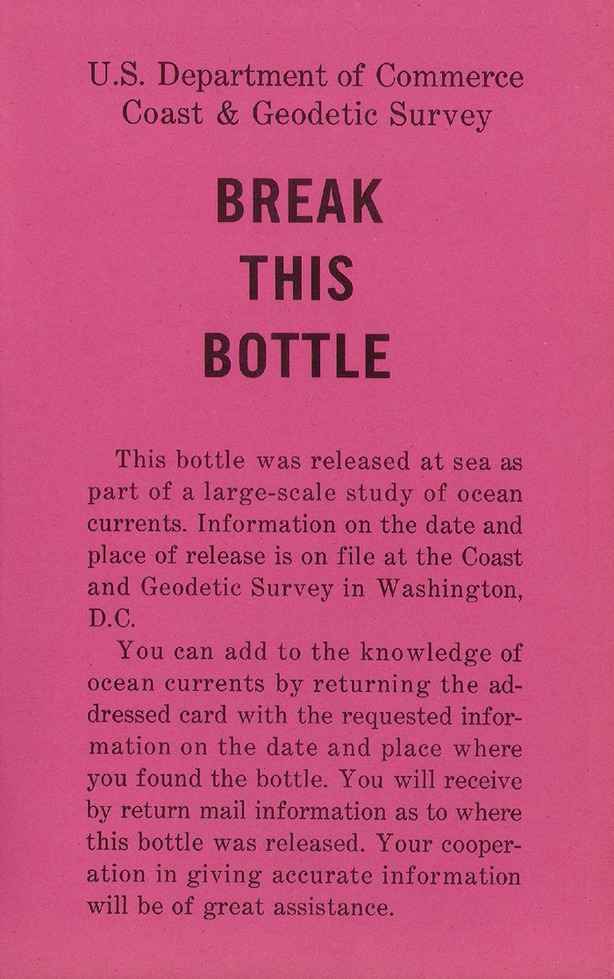

The use of drift bottles continued for decades after Brown's experiment. Here's one gloriously pink card included in American oceanographic studies from circa 1960.

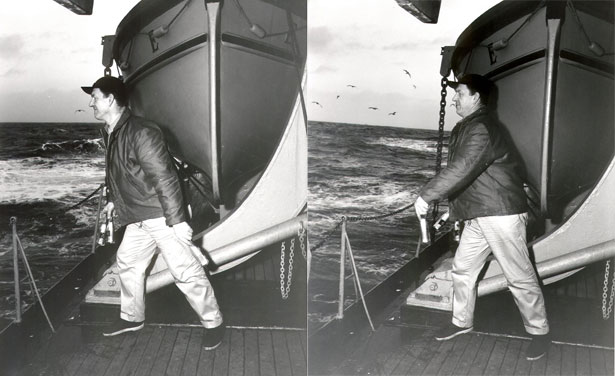

And here's the kind of guy who was tossing those bottles overboard hoping that someone would find them and return the data, according to the NOAA photo archives.

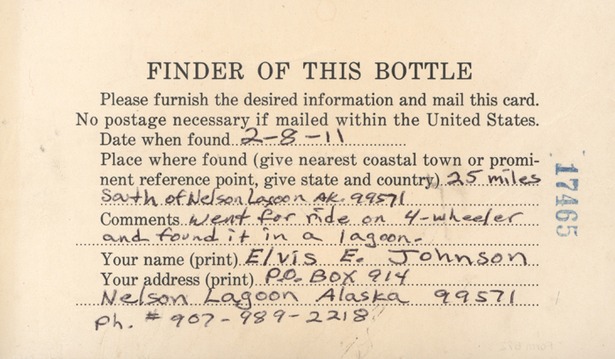

And this is the last drift bottle card that Americans have collected, a gem from Alaska in 2011. Thanks, Elvis.

* This story initially incorrectly used C. Hunter Brown's middle name instead of his last to refer to him throughout the story. This has been fixed and I regret the error.

Via @elikint