Mortise and Tenon: A Primer - Woodworker's Journal

Mortise and Tenon: A Primer - Woodworker's Journal

Mortise and Tenon: A Primer - Woodworker's Journal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

32<br />

<strong>Mortise</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tenon</strong>: A <strong>Primer</strong><br />

Joining long grain to end grain with mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon — the king of rail joints<br />

By Ian Kirby<br />

A<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon joint is<br />

nothing more than a square<br />

peg in a square hole. The joint<br />

is either stopped or through. The<br />

through joint is usually wedged,<br />

which makes it effectively a dovetail<br />

joint. Chances are there isn’t a house<br />

in the U.S.A. that doesn’t have<br />

examples of the joint somewhere in<br />

its furniture or built-in cabinets.<br />

In this article I’ll describe the<br />

three main ways the joint is used.<br />

Since the geometry of any design<br />

follows a certain set of conditions,<br />

it’s vital to underst<strong>and</strong> that aspect of<br />

the joint. I’ll also explain how to<br />

design for strength.<br />

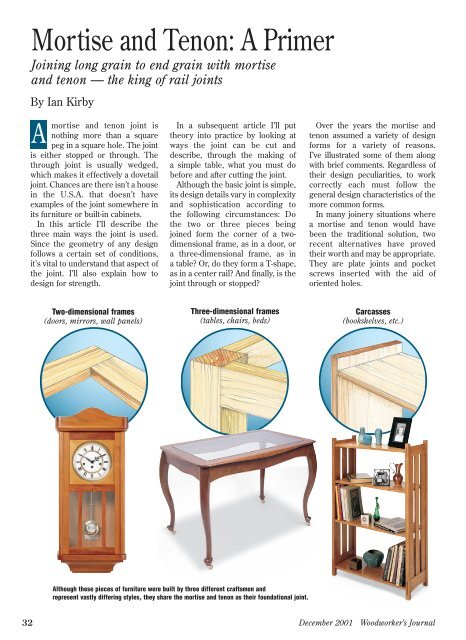

Two-dimensional frames<br />

(doors, mirrors, wall panels)<br />

In a subsequent article I’ll put<br />

theory into practice by looking at<br />

ways the joint can be cut <strong>and</strong><br />

describe, through the making of<br />

a simple table, what you must do<br />

before <strong>and</strong> after cutting the joint.<br />

Although the basic joint is simple,<br />

its design details vary in complexity<br />

<strong>and</strong> sophistication according to<br />

the following circumstances: Do<br />

the two or three pieces being<br />

joined form the corner of a twodimensional<br />

frame, as in a door, or<br />

a three-dimensional frame, as in<br />

a table? Or, do they form a T-shape,<br />

as in a center rail? And finally, is the<br />

joint through or stopped?<br />

Three-dimensional frames<br />

(tables, chairs, beds)<br />

Although these pieces of furniture were built by three different craftsmen <strong>and</strong><br />

represent vastly differing styles, they share the mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon as their foundational joint.<br />

Over the years the mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenon assumed a variety of design<br />

forms for a variety of reasons.<br />

I’ve illustrated some of them along<br />

with brief comments. Regardless of<br />

their design peculiarities, to work<br />

correctly each must follow the<br />

general design characteristics of the<br />

more common forms.<br />

In many joinery situations where<br />

a mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon would have<br />

been the traditional solution, two<br />

recent alternatives have proved<br />

their worth <strong>and</strong> may be appropriate.<br />

They are plate joints <strong>and</strong> pocket<br />

screws inserted with the aid of<br />

oriented holes.<br />

Carcasses<br />

(bookshelves, etc.)<br />

December 2001 Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong>

Anatomy of Parts<br />

A key step to underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon joinery is<br />

knowing the parts, many of which<br />

are derived from human anatomy.<br />

The specific name of the<br />

mortise/tenon piece depends upon<br />

its function <strong>and</strong> orientation. The<br />

mortise piece is usually the upright<br />

member, such as a stile, leg, or<br />

post. The tenon piece is usually<br />

horizontal, such as a rail, an apron,<br />

a stretcher, or a shelf.<br />

Dimensions of Parts<br />

A = <strong>Tenon</strong> length = <strong>Mortise</strong> depth<br />

On a stopped joint leave a gap<br />

between the end of the tenon <strong>and</strong><br />

the bottom of the mortise. The two<br />

parts don’t need to meet since the<br />

end grain of the tenon isn’t a gluing<br />

surface, <strong>and</strong> it’s easier to make if<br />

you leave a gap of about 1/16".<br />

B = <strong>Tenon</strong> width = <strong>Mortise</strong> length<br />

Make the tenon width to exact fit. If<br />

it’s too narrow, the tenon may float<br />

<strong>and</strong> position the rail in the wrong<br />

place. For the same reason, don’t<br />

crush the the edges of the tenon<br />

during assembly thinking you are<br />

making the joint tight. More likely<br />

you are causing misalignment. The<br />

end walls of the mortise are end<br />

grain <strong>and</strong> therefore not suitable<br />

gluing surfaces.<br />

Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong> December 2001<br />

<strong>Mortise</strong><br />

piece<br />

Stile<br />

End<br />

wall<br />

Bottom<br />

Cheeks<br />

B<br />

A<br />

C<br />

Defining the parts<br />

Side wall<br />

B<br />

C<br />

End<br />

C = <strong>Tenon</strong> thickness = <strong>Mortise</strong> width<br />

Make the tenon width to exact fit. If<br />

it’s too thin, it will likely float <strong>and</strong><br />

position the rail in the wrong place.<br />

You should be able to “push fit”<br />

the parts together. A “clamp fit”<br />

with squeaky resistance is too tight.<br />

Applying glue will swell an easy-fit<br />

joint much tighter. A too-tight joint<br />

might split when glue is added.<br />

Geometry of Parts<br />

Accurate joinery, whether cut by<br />

h<strong>and</strong> or machine, is defined by<br />

accurate geometry.<br />

Some authors recommend undercutting<br />

the shoulder to ensure<br />

a tight-fitting joint. My view is —<br />

don’t. First, what is undercut? 85°?<br />

70°? Second, how do you measure<br />

it? Third, if you can undercut<br />

consistently, its st<strong>and</strong>s to reason<br />

you can also cut square.<br />

Shoulders square to face<br />

side <strong>and</strong> other faces<br />

Faces aligned with stock,<br />

with no twist<br />

A = <strong>Tenon</strong> length = <strong>Mortise</strong> depth<br />

B = <strong>Tenon</strong> width = <strong>Mortise</strong> length<br />

C = <strong>Tenon</strong> thickness = <strong>Mortise</strong> width<br />

A<br />

Face<br />

Edge<br />

Cosmetic<br />

shoulder<br />

<strong>Tenon</strong><br />

piece<br />

Rail<br />

Structural<br />

shoulder<br />

The undercut shoulder presents<br />

an edge to the stile instead of a flat<br />

face. Clamp pressure easily pushes<br />

the edge into the stile, distorts the<br />

wood, <strong>and</strong> changes the between-theshoulders<br />

distance. Most important,<br />

you also lose the mechanical<br />

efficiency of a dead stop.<br />

<strong>Mortise</strong> <strong>and</strong> tenon joinery is<br />

subjected to two types of stress.<br />

One type arises from use, as when<br />

we lean back in a chair or push<br />

a table to a new location. The other<br />

type arises from wood movement.<br />

Wood shrinks <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>s across<br />

the grain in response to changing<br />

humidity but not along its length.<br />

To cope with both types of stress,<br />

we design the joint to be as strong<br />

as possible. Since the configuration<br />

<strong>and</strong> section of the parts being<br />

joined are usually unique, we must<br />

design for the job at h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> that<br />

design is based on experience<br />

about what has worked before.<br />

End walls square to the<br />

face side <strong>and</strong> face edge<br />

Side walls parallel to each<br />

other <strong>and</strong> to face side

34<br />

Designing for strength<br />

Shoulders<br />

All tenons require shoulders. There<br />

are two types. Structural shoulders<br />

resist bending stress. Cosmetic<br />

shoulders hide the joint if the rail<br />

shrinks <strong>and</strong> they hide the gap<br />

presented by a damaged mortise<br />

end or a mortise made slightly<br />

long. Cosmetic shoulders need be<br />

only 1/8" to be effective.<br />

A tenon without a shoulder on<br />

one side is called a barefaced<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon. To keep it<br />

aligned at the glue-<strong>and</strong>-clamp stage<br />

requires purpose-made clamping<br />

blocks. I don’t recommend this<br />

configuration. If at all possible,<br />

reduce the thickness of the tenon to<br />

get a shoulder on each side.<br />

No shoulder<br />

on this face<br />

A tenon without a shoulder on one face of the<br />

stock, called a barefaced mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon,<br />

is not recommended. Try reducing the tenon<br />

thickness to get a shoulder on the bare side.<br />

<strong>Tenon</strong> Length, <strong>Mortise</strong> Depth<br />

If the tenon is too long, the joint is<br />

under greater stress due to wood<br />

movement. Too short, <strong>and</strong> it may<br />

fail due to too little glue surface. My<br />

compromise is to mortise about<br />

halfway into the stile. In narrow<br />

stock, go a bit more than halfway.<br />

Horn<br />

1/16"<br />

gap<br />

<strong>Tenon</strong> is<br />

too thin<br />

for<br />

typical use<br />

1 ⁄3 1 ⁄3<br />

1 ⁄3<br />

When a mortise is placed near the end of a stile,<br />

an extra inch of so of material is left to extend<br />

past the joint. This horn will be cut off later.<br />

<strong>Tenon</strong> Width, <strong>Mortise</strong> Length<br />

If a mortise extends too near to<br />

the end of the stile of a corner<br />

joint (often, exactly the spot<br />

where you simply need a joint to<br />

go), the stile may split. Therefore,<br />

make the tenon shoulder nearest<br />

the end of the stile one-quarter<br />

the total width of the<br />

tenon. To keep from<br />

splitting the mortise,<br />

an extra inch or so<br />

(called the horn) is<br />

left on the stile. Once<br />

the glue is cured <strong>and</strong><br />

the job is out of<br />

clamps, the horn is<br />

sawn off.<br />

When the mortise is<br />

not at the end of the<br />

stile, make the tenon<br />

the full width of the<br />

rail, less 1/8" at each<br />

edge for the cosmetic<br />

shoulder.<br />

Preferred<br />

machining<br />

of the<br />

joint<br />

3<br />

⁄16<br />

" 3<br />

⁄8<br />

" 3 "<br />

⁄16<br />

Make the tenon<br />

shoulder nearest<br />

the end of the stile<br />

1/4th the total<br />

width of the tenon.<br />

MORTISE & TENON RULES<br />

1. Hidden mortises should penetrate<br />

about halfway into a stile.<br />

2. Create Balanced joints.<br />

3. Structural shoulders resist stress.<br />

4. Cosmetic shoulders hide the joint.<br />

5. At the end of a stile, leave a horn.<br />

(to resist splitting)<br />

6. Don’t undercut.<br />

When joining two pieces of the same thickness,<br />

balancing the joint for strength amounts to<br />

making the thickness of the two cheeks added<br />

together equal the thickness of the tenon.<br />

<strong>Tenon</strong> Thickness, <strong>Mortise</strong> Width<br />

When joining two pieces of wood of<br />

the same thickness, divide the<br />

thickness roughly in half to create<br />

a balanced joint. For example, if the<br />

wood is 3/4" thick, make the tenon<br />

3/8" thick <strong>and</strong> each mortise cheek<br />

3/16" thick. Since each piece has an<br />

equal amount of tissue, each is<br />

equally able to resist stress <strong>and</strong> the<br />

joint is balanced.<br />

Loose-tenon Joint<br />

A slot mortiser is a machine that<br />

cuts a mortise into both rail <strong>and</strong><br />

stile. The two parts are connected<br />

with a third piece made to fit the<br />

slot, much like a biscuit joiner. This<br />

joint is called a loose mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenon. You can make the joint using<br />

a plunge router <strong>and</strong> a single bit,<br />

although you will normally need<br />

different jigs to manage the two<br />

parts. Once glued, the joint is just<br />

as strong as a conventional mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon.<br />

Floating <strong>Tenon</strong><br />

Loose tenon joints are the<br />

inspiration for latter-day biscuit<br />

joiners. Once glued in place they<br />

are as strong as a traditional<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon joint.<br />

December 2001 Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong>

Two-dimensional frames<br />

<strong>Mortise</strong><br />

& <strong>Tenon</strong><br />

Variations<br />

Nearly as soon<br />

as there were<br />

woodworkers, the mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon joint was<br />

created — an efficient<br />

<strong>and</strong> elegant way to join<br />

solid wood. Variety being<br />

the spice of life <strong>and</strong> the<br />

essence of creativity,<br />

many kinds of mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon joints became<br />

common. Due to advances<br />

in machinery, adhesives,<br />

<strong>and</strong> techniques, the<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon<br />

variations illustrated here<br />

are seldom used today.<br />

Long<br />

<strong>and</strong> short<br />

shoulder<br />

mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon<br />

Frame <strong>and</strong> Panel<br />

Two-dimensional frames with a solid panel<br />

trapped in a groove make a classic frame<br />

<strong>and</strong> panel. This ingenious construction is<br />

not only the foundation of furniture<br />

making, it remains the only method we<br />

have for making a dimensionally stable<br />

frame from dimensionally unstable solid<br />

wood. The traditional example is, of course,<br />

the frame <strong>and</strong> panel door. Although with<br />

modern material this door is no longer the<br />

most efficient design available, tradition<br />

<strong>and</strong> a sense of history continue to drive the<br />

popularity of this beautiful cabinet staple.<br />

Used in multiples, we can make larger<br />

frames, which, joined at the corners, make<br />

storage chests <strong>and</strong> cabinets.<br />

Haunch<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenon<br />

1<br />

⁄4<br />

A stile turned 90˚ to<br />

the rail provides the<br />

greatest resistance to<br />

stress. Typically the<br />

through tenon in that<br />

situation will be 1/4th<br />

the width of the rail.<br />

Fox tail wedge<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenon<br />

As the rail is driven<br />

home, the wedges<br />

exp<strong>and</strong> the tails.<br />

In the days of h<strong>and</strong> tool<br />

woodworking, grooves<br />

were made using a plow<br />

plane. Because you can’t<br />

make a stopped groove<br />

with a plow plane, the<br />

haunch was left on the<br />

tenon to fill the groove.<br />

If the frame was to be<br />

fitted with a glass panel<br />

sitting in a rabbet, then<br />

the long <strong>and</strong> short joint<br />

was used.<br />

The author has<br />

made many fox<br />

tail joints but<br />

never used one in<br />

furniture! You only<br />

get one shot at<br />

glue-up. It’s<br />

a clever concept,<br />

but there’s no<br />

place in furniture<br />

where it’s really<br />

necessary.<br />

MORTISE & TENON RULES<br />

7. The completed joint<br />

should slide together with<br />

moderate h<strong>and</strong> pressure.<br />

8. Accurate geometry is the<br />

key to effective joinery.<br />

9. With stopped tenons,<br />

always cut them 1/16"<br />

short of the end wall.<br />

10. Use a sufficient amount<br />

of glue on the joints (but<br />

avoid over gluing.)<br />

A middle rail A top rail<br />

Balanced<br />

cosmetic<br />

shoulders<br />

<strong>Mortise</strong> <strong>and</strong> tenons <strong>and</strong> the flat<br />

panels easily created by them have<br />

long been the building blocks of solid<br />

wood construction. Adjust the<br />

position of the tenon at the end of<br />

the rail to logically suit the location<br />

of the rail in the panel.<br />

Sloping<br />

haunch<br />

mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon<br />

Pegged<br />

mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon<br />

By slightly offsetting<br />

the through tenon, you<br />

can reduce your<br />

chances of splitting<br />

the stile <strong>and</strong> add<br />

stability to the joint.<br />

Shoulder<br />

is offset<br />

from top<br />

of joint<br />

to avoid<br />

splitting.<br />

On a threedimensional<br />

frame,<br />

there is no need for<br />

a groove. The notion<br />

of a haunch,<br />

however, remained.<br />

A sloping haunch<br />

satisfies the<br />

psychological need<br />

for a haunch <strong>and</strong><br />

the visual need for<br />

a flush shoulder line<br />

at the top edge.<br />

Draw pegging<br />

is a technique<br />

derived from<br />

timber frame<br />

construction. It’s<br />

unnecessary with<br />

modern glues <strong>and</strong><br />

correctly made<br />

joints, but if you<br />

like the look, add<br />

the pegs after<br />

the joint is made.<br />

Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong> December 2001 35

Tables, chairs<br />

<strong>and</strong> other<br />

pieces of<br />

furniture are<br />

created from<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenon joints<br />

constructed<br />

in three<br />

dimensions.<br />

36<br />

Three-dimensional frames are<br />

used to make table bases, chairs,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the skeletons of large cases.<br />

Three members generally connect,<br />

for example, a table leg <strong>and</strong> two rails<br />

or aprons. In most situations the<br />

vertical leg is more or less square in<br />

section, while the incoming rails are<br />

flat. Factors affecting the design of<br />

the joint include the width <strong>and</strong><br />

thickness of the rails, the exact<br />

location of the rails on the faces of<br />

the leg, <strong>and</strong> complications caused<br />

by drawers or doors.<br />

Underframes impart stability<br />

to a piece of furniture. On this one<br />

the design not only includes twin<br />

tenons, but wedged tenons as well.<br />

Three-dimensional frames<br />

Inset Rails<br />

Flush Rails<br />

Centered<br />

Rails<br />

The illustrations above show<br />

the rail in three different place on<br />

the leg. Once the joint is glued, the<br />

“flush rail” must be made dead<br />

flush by planing — a manufacturing<br />

detail unnecessary with the inset<br />

rail. However, the strongest reason<br />

to inset the rail is visual: the change<br />

in level, along with the associated<br />

highlights <strong>and</strong> shadows, emphasizes<br />

the vertical element of the leg.<br />

Leg<br />

Stretcher<br />

Crossbar<br />

With three<br />

dimensional frame<br />

construction,<br />

design<br />

considerations<br />

become almost<br />

infinitely variable.<br />

Regardless of how<br />

the joint is<br />

employed to<br />

create a pleasing<br />

appearance, the<br />

rules of mortise<br />

<strong>and</strong> tenon joinery<br />

must be observed.<br />

Note that the thickness of the<br />

tenon is increased as it is inset while<br />

the gluing area decreases. In each<br />

case the tenon is mitered in the<br />

middle of the joint. Provided the<br />

tenons don’t touch, you can make<br />

the gap as small as you like. The<br />

1/8" inside shoulder on the flush<br />

<strong>and</strong> inset rail is enough to do the job.<br />

Underframes<br />

Underframes impart stability to<br />

a piece of furniture by bracing the<br />

structure. They often do double<br />

duty as supports for shelves.<br />

Where two underframe members<br />

meet at a T-shaped junction, you<br />

can increase the gluing area by<br />

using twin tenons. If the joint is<br />

made through <strong>and</strong> wedged, it offers<br />

an attractive design detail.<br />

Twin <strong>Tenon</strong>s<br />

When the rail is thicker than 1", you<br />

can increase the gluing area by<br />

making twin tenons side by side.<br />

The total thickness of the two<br />

tenons is about the same as for<br />

a single tenon, but the doubled<br />

gluing area makes for a potentially<br />

stronger joint. The figure below<br />

shows typical proportions: the<br />

minimum thickness of each tenon<br />

is about 3/16", <strong>and</strong> the space<br />

between should be about equal the<br />

tenon thickness. Twin tenons are<br />

often used this way in chair making<br />

where a back rail joins a legs.<br />

Thicker stock offers the possibility of creating<br />

twin tenons. The key advantage to this<br />

modification is you nearly double the glue area.<br />

December 2001 Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong>

Short twin tenons also occur in<br />

carcass sides, where a partition ties<br />

the case together <strong>and</strong> also acts as<br />

a shelf. Make the housing (also<br />

known as a dado) about 1/8" deep<br />

between the mortises. A housing<br />

between tenons not only makes the<br />

shelf able to bear a heavy load, but<br />

it also flattens any cup in the two<br />

boards. Because the tenons would<br />

otherwise be very short, they are<br />

usually made through <strong>and</strong> wedged.<br />

Because of the 1/8" deep housing,<br />

a 1/2" thick tenon is plenty big.<br />

Stop<br />

short by<br />

1/4".<br />

Gradient<br />

1 = 8<br />

Wedge is 1/8"<br />

longer than<br />

the kerf.<br />

A through-wedged mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon dem<strong>and</strong>s<br />

precision joinery. The wedge must thrust the<br />

stock against the end grain of the mortise.<br />

Place it the other way <strong>and</strong> you’ll split the wood.<br />

Gluing <strong>and</strong> Clamping<br />

A simple yet elegant idea like the<br />

mortise <strong>and</strong> tenon joint can go<br />

wrong at the last moment. In a later<br />

article, I’ll go through the basics of<br />

gluing <strong>and</strong> clamping. But for now<br />

I must simply say that incorrectly<br />

applied clamps <strong>and</strong> their critically<br />

important clamping blocks, or<br />

cauls, will ruin the best crafted<br />

joints in short order. So do not give<br />

short shrift to this last step in<br />

making a joint.<br />

With these few concepts in mind,<br />

it’s time to go to your shop <strong>and</strong> join<br />

some wood. Good cutting!<br />

Carcasses<br />

MORTISE & TENON RULES<br />

11. Don’t think you can make accurate<br />

mortises by drilling the waste away<br />

<strong>and</strong> “cleaning up” with a chisel. If you<br />

don’t form your mortises entirely by<br />

h<strong>and</strong>, try these easy to follow<br />

steps.<br />

Ian’s recommended process:<br />

a. After marking the joint, use an<br />

appropriate drill bit to<br />

carefully remove most of<br />

the waste.<br />

b. Use a plunge router <strong>and</strong><br />

a router jig to further<br />

machine the mortise.<br />

This will give you parallel<br />

walls square to your<br />

work piece.<br />

c. Pare the corners<br />

square <strong>and</strong> true with<br />

a sharp chisel.<br />

One place where through mortise <strong>and</strong><br />

tenons, <strong>and</strong> particularly twin tenons, occur<br />

regularly is in projects such as a bookcase.<br />

The through tenons are both structurally<br />

integral <strong>and</strong> visually beautiful. An additional<br />

joinery technique that the author regularly<br />

employs is a conjoined housing (or a dado<br />

here in America). The 1/8" deep dado<br />

shown between the mortises increases<br />

the weight-bearing capabilities of the shelf<br />

<strong>and</strong> flattens any cupping in the shelf <strong>and</strong><br />

upright pieces. It also presents a clean<br />

<strong>and</strong> subtle joint line.<br />

In this example, the author recommends a shallow<br />

dado stretching between the through mortises.<br />

Woodworker’s <strong>Journal</strong> December 2001 37