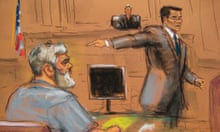

It was said that even the Queen questioned why Abu Hamza, the firebrand preacher of the Finsbury Park mosque who had been ridiculed in the tabloid press as 'Hooky the panto villain', had not been prosecuted in a British court.

"The Queen was pretty upset that there was no way to arrest him. She couldn't understand - surely there had been some law that he had broken?" the BBC's security correspondent Frank Gardner reported in 2012 when Hamza was battling against his extradition to the US.

The Queen, along with many others, was puzzled why Hamza had not been arrested and put on trial years before he was finally convicted and sentenced in 2006 to seven years for soliciting murder and inciting racial hatred in his inflammatory Finsbury Park "sermons".

The then shadow home secretary, David Davis, even claimed at the time that the only reason that Hamza had actually been prosecuted at all was that the Americans were seeking his extradition.

This view was fuelled by the evidence that for many years while Hamza with his hook hand and blind eye was demonised as the face of radical Islam in Britain in the tabloid press, the security services were slow to respond and regarded him as a harmless rabble-rouser. "He was seen as all mouth and no trousers," said one informed security source. Indeed Hamza himself claimed to have had half a dozen meetings with MI5 in which he was led to believe his speeches were "unwelcome but lawful."

The lack of official action also appeared to give substance to "Londonistan"-style claims that the Finsbury Park mosque was a global magnet for militants while Hamza ran it from the late 1990s until 2003.

The curious thing is that Scotland Yard started its own investigation into the kidnapping of 16 western tourists in the Yemen, including three Britons who were killed, – one of the three main charges Hamza faced in New York this week – at the same time as the American FBI. Scotland Yard anti-terrorist branch officers had got a plane to Yemen within two days of the attack on 29 December 1998.

That Scotland Yard investigation concluded that there was a link between Yemen kidnapping and a planned bombing campaign of western targets by a six-strong group arrested in Aden called "the supporters of Sharia". Hamza appeared on British television and admitted he was in contact with the Yemen kidnappers and that one of the suspects was possibly his stepson, but denied any criminal involvement himself.

The high court in London heard in 2008 that an undated Metropolitan police report concluded in 1999 that Hamza should not be prosecuted for any involvement in the Yemen hostage taking offences despite the deaths of three Britons.

"The report expressed itself in unequivocal terms, that links between the appellant and the hostage takers were established, but it continued 'evidentially the links have proved inconclusive, and rely heavily on information gathered from Yemeni sources which would not ordinarily be admissible during a British trial … there does not appear to be evidence to prove that Abu Hamza … conspired with the kidnappers to bring about the kidnap or deaths of the tour groups hostages although suspicions will always remain'," said Mr Justice Sullivan when rejecting one of many appeals by Hamza against his extradition.

There was only one British link to the two other major charges that Hamza was convicted of this week in New York – those of being involved in setting up a terrorist training camp in Bly, Oregon and providing support to terrorists in Afghanistan. The link was a British citizen called Feroz Abbasi who was arrested in Afghanistan and detained in Guantanamo Bay. The defence claimed that he subjected to torture during this period and any reliance on his evidence would have been strong disputed as inadmissible. In the event the Americans expressly retracted any reliance on his testimony.

Mr Justice Sullivan ruled in 2008 that he was convinced that any prosecution against Hamza for the Yemen kidnapping only "became viable" in 2003 when the FBI became aware of a recorded interview in 2000 between Hamza and Mary Quinn, an American hostage who had been seriously injured in the kidnapping, in which he incriminated himself. Shortly afterwards a second US citizen, James Ujaama, who had been at the Oregon training camp, provided evidence linking Hamza with the Oregon and Afghanistan conspiracies.

The issue of whether Hamza could be prosecuted in Britain rather than extradited to America was finally settled by the European Court of Human Rights in 2011.

When the European judges dismissed his final appeal they rejected claims for a British trial saying that the evidence of the surviving British hostages wouldn't be helpful in determining whether or not Hamza's involvement was criminal.

Instead a British trial would be plagued by claims that 'the nature and quality' of the pre-trial publicity – the relentless portrayal of Hamza as a James Bond pantomine villain – would make a fair trial impossible. More importantly a UK trial would lack the live evidence from the two crucial American witnesses, Ujaam and Quinn, that was critical to a successful prosecution.

Both British and European judges also went out of their way to reject the "innuendo" that the decision not to prosecute in Britain was "tainted by some improper collusive agreement with the authorities in the United States to leave the responsibility for bringing criminal charges against the appellant to them. There is not the slightest evidence to justify it," they said.

The judges did however add that it remained "unclear" as to why the police, and by implication the security services, hadn't regarded Hamza's firebrand preaching as sufficient grounds to prosecute him under British law in 1999 but did in 2004. MI5 now seem to acknowledge that, with hindsight, in the case of Hamza they were mistaken in branding him "all mouth and no trousers".

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion