Professor Brian Cox is advanced fellow of particle physics in the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Manchester. He is about to embark on a nationwide tour to promote the ideas in his new book, Universal: A Guide to the Cosmos.

I was looking through your tour dates. You are playing Wembley…

The bigger the venue the fewer people you can see is a general rule. It’s just great that cosmology can get people out. I did another event at Wembley Arena for 8,000 children, which was brilliant.

There is an evangelical cast to what you do, turning people on to science. When you see those children’s faces light up does it feel like a conversion experience might feel?

Astronomy is something that kids are just interested in –like dinosaurs. And especially with pictures from the planets now. With the New Horizons pictures from Pluto all the kids were fascinated particularly because they feel for Pluto because it is no longer a planet. It got demoted recently. It was a big thing in schools, partly because Pluto was named by a child in the first place.

Your new book feels like a sort of magnum opus, a statement of where you – and co-author Jeff Forshaw – think we are up to in relation to the universe…

Yes. I’ve worked with Jeff for 20-odd years now. We’ve written loads of papers together. The book started off sort of as a manual of what it means to take a scientific approach to nature. But it did turn into a book more about cosmology. And that’s really because we both academically have been getting really into this theory of “inflation”, this theory of the exponential expansion of the universe before the Big Bang as we define it. But the overall idea of the book was to start with some things you could imagine doing yourself in your back garden or on the beach in Wales – and then by the time you get to the stuff where you need a space telescope you don’t mind because you know the process. It’s a book about how to think.

And also how to look?

Yes, what to pay attention to. I love that you can measure the motion of the planets across the sky yourself with a standard camera. The fact that you can measure the distance of something right on the edge of the solar system from your back garden, I think is culturally important. It’s not important to know exactly what the distance is for everyone, but to make that connection, to verify for yourself that these things can be done.

Strangely, though, we as a culture probably look at the night sky less often than any human beings in history, partly because of light pollution but also because we can no longer really project meaning on to it in the way that cultures have always done in the past. I guess there is only so much meaninglessness that we can cope with…

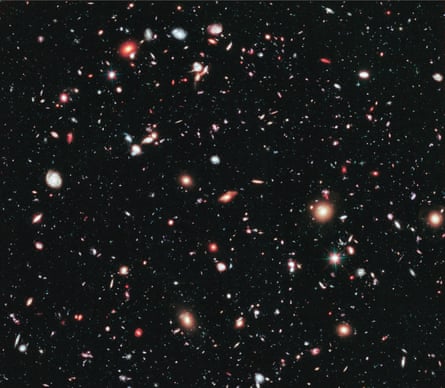

Way back, when we started to do the stargazing programmes on the BBC, one of the reasons to do it was just to get people to look up occasionally. Even in the middle of London you can still see Venus and Jupiter. And it’s a wider state of mind, people increasingly don’t look beyond themselves, they are becoming ghettoised politically in the same way. To me cosmology is the most powerful way of gaining perspective. When you can see the Andromeda galaxy with the naked eye, and it’s two and a half million light years away, it should at least get you to think a little bit about our place in the universe.

I spent some evenings a while ago doing that Galaxy Zoo project, classifying galaxies on my laptop for the crowdsharing science project. It was weird - partly it fires a sense of wonder, but also it was just looking at another thing on a screen. Have we lost a sense of looking without mediation?

Looking carefully is the foundation of modern civilisation. Close observation is the way we managed to do things like build transistors, or the electric motor. It seems to me more than ever in a democratic society based on scientific principles, people should be required to have at least a passing acquaintance with the system of thought that led to that society. If people don’t have that then when you are presented with a serious piece of science, like public health policy or whatever, you don’t know what weight to give the scientific voice. That is not to say that scientists should be making the decisions in society. But the public should be able to weigh what it means when people say “the scientific consensus is this”. We need to address that in schools a little bit more.

It seems to me that the drift of education is towards the importance of having an opinion, without necessarily an underpinning of knowledge. That is why it is so unforgivable for someone like Michael Gove to make a pejorative of “experts”. As if enlightenment were just a project…

The idea that people have a right to their opinion is obviously true in a free society. But you really do not have a right to have that opinion heard. The weighting has to be toward knowledge. Everyone bemoans the state of politics at the moment and points toward the media or social media, and that’s a complicated discussion. But the point is for one reason or another many people don’t know how to change their mind. The whole point of science is that you have to be prepared – and delighted – to change your mind in the face of new evidence. That is the message that should be taught in schools.

In that sense it has always seemed to me odd that scientists – and I’m speaking very broadly obviously – tend toward atheism rather than agnosticism. If anything, shouldn’t their faith be in doubt?

Coincidentally yesterday I gave a cosmology lecture to 400 Church of England vicars in Liverpool. There was a Q and A session for an hour and a half afterwards. Not once did the question of whether I was an atheist come up. They weren’t interested, and I’m not interested in that question. It never crosses my mind to be honest. I mean it would never occur to me to invent a God to believe in…

Of course – but then there is the wider question of the universe being something rather than nothing?

The question of what meaning is came up at this conference. It has always been self-evident to me that there is meaning in the universe, because the universe means something to me. We all care about our family and our kids so obviously meaning exists. But it seems to me the question is whether that meaning is local and temporary to the Milky Way. I’m perfectly happy to think that might be the case.

I remember talking to the cosmologist Paul Davies once, who seemed to tend to the view that the universe is somehow geared to understanding itself; all his observation led him to that conclusion. Can you sympathise with that idea?

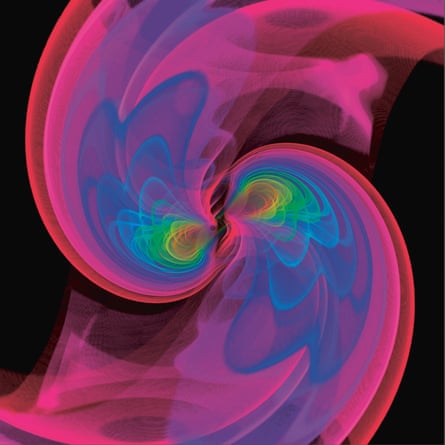

I don’t have that belief. It’s the final anthropic principle: that there is something about the consistency of the universe that makes it necessary to be understood. I don’t think that. In the book we talk about this idea of the inflationary multiverse. It’s still a guess, but most cosmologists are tending toward that theory, I’d say.

How far are the dots apart for you to make that leap of understanding?

The theory of inflation itself is almost nailed down. We teach it at undergraduate level, and the data supports it as far as we can tell. The idea of multiverses is not too big a leap from that. If that is right then you have essentially an infinity of universes and it follows there is a very natural, almost unavoidable mechanism for varying the laws of nature in each universe. Therefore the idea that we look out on a universe that has been waiting for us to appear in it and understand it is at best incidental. Because every possible sort of universe is made real by inflationary cosmology.

I’m a sucker for a Douglas Adams quote, at this point: “There is a theory which states that if ever anybody discovers exactly what the universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened…”

I like Arthur C Clarke’s 1953 story The Nine Billion Names of God: Monks commission a super computer to use this algorithm they have created to tell them the 9 billion names of God, which they believe is the purpose of humanity. The computer company goes along with it. At the end of the story the computer engineers, who have been laughing at the monks, switch on the program, and the story ends with the great line, “One by one the stars started going out”.

Were you an avid reader of science fiction as a kid?

Yes, I particularly liked Arthur C Clarke and Isaac Asimov.

Never been tempted to have a crack at fiction yourself?

Only in the way I have been tempted to have a crack at being a Premier League footballer.

You must get into theories of perception a lot at your end of science. With that in mind have you seen the value of hallucinogenics to shift your understanding?

No, I’m from what Richard Feynman calls the “shut up and calculate school”. Whatever you think about quantum mechanics, the role of the observer is quite slight, the science predicts probabilities very precisely and suggests that if you know how particles move around and bump into each other and do a bit of calculation you can build a transistor. It’s great. You can have loads of arguments about perception but the role of science is to make models, in my view, and you take measurements and make models and you see if the model describes nature. Take general relativity, for example. You have this model called space-time, which curves and warps in the presence of mass. Is space-time real? Is it a real thing? Is the universe really a fabric? I don’t know – but I do know the model works brilliantly.

Is it important or possible to have mental pictures of such things?

There are two ways of doing it. You can just do the mathematics, or you can try to build pictures. Einstein was in the latter camp, he looked for intuitive pictures and used the mathematics afterwards. And if it worked for Einstein…

In your TV shows you always seem to be flooded with excitement about what you are describing. Are you always searching for those moments?

The thrill of understanding is something all people who have studied science understand. There is a tremendous elegance to our understanding of nature. Even if you learn for yourself things that many other people know. It is a unique feeling. As I’ve said before, it is the difference between looking at the score of Mahler’s ninth and then going to listen to it.

Universal: A Guide to the Cosmos by Brian Cox and Jeff Forshaw is published on Thursday by Penguin (£25). Click here to order it for £20.50. Extra dates are available for Professor Brian Cox Live. See ticketmaster.co.uk/briancox for details

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion