Sigur Rós’s new album Átta, their first in a decade, is a tender and consoling piece of work that seems to extend a healing hand to the listener. Given the dramatic events in the band members’ lives during its long gestation, you suspect it serves a similar purpose for the Icelanders themselves. “It’s a comfort blanket for us maybe,” agrees frontman Jón Þór “Jónsi” Birgisson from his home in Silver Lake, Los Angeles. The period the album emerged from was, he says, “depressing and heavy and intense”.

In March 2018, the Icelandic government accused Sigur Rós of evading 151m króna (£840,000) of tax between 2010 and 2014. The band blamed an accounting error and repaid the debt plus interest, but faced a second prosecution for the same offence in 2020, which froze their assets. They have all now been acquitted but Birgisson has been off the hook only since March. And that was not all. In September 2018, artist Meagan Boyd publicly accused drummer Orri Páll Dýrason of sexual assault five years earlier. Dýrason denied the allegations but resigned a few days later, temporarily reducing Sigur Rós to a transatlantic duo of Birgisson and bassist Georg “Goggi” Hólm. Did it still feel like a band at all?

“It was strange,” says Hólm, sitting in the band’s Reykjavik headquarters with returning keyboardist Kjartan Sveinsson (who had left the band in 2013). Now in their late 40s, they look like mismatched detectives reuniting on a cold case in a Nordic noir show. “There were definitely points when me and Jónsi would go, well, I guess we’re a band but we’re not really doing anything.” Amid all of this, Birgisson split from Alex Somers, his partner of 16 years and frequent artistic collaborator. A band whose music inspired breathless celestial metaphors seemed to fall to earth with an ugly thud. “Our main purpose is the music but obviously there is this thing called life that happens around it and you have to deal with it,” says Hólm.

When Sigur Rós formed in 1994 as teenagers, Birgisson says, they made music because “it gives you a purpose to live and be happy”. As a non-anglophone post-rock band from a “tiny little island in the middle of nowhere”, they didn’t exactly dream of Madison Square Garden, but their second album, 1999’s Ágætis byrjun, was a word-of-mouth phenomenon whose cheerleaders included Radiohead, Coldplay, David Bowie and Cameron Crowe. In a genre with a forbiddingly studious reputation, Sigur Rós had an elemental grace and a direct line to one’s tear ducts. “If I don’t get goosebumps, then we have to work a bit more,” says Sveinsson. “Of course, you have to be careful not to go full Disney on it. You’re playing with emotions, but you don’t want to force-feed it. It’s not like foie gras.”

What happened next is a familiar story: young band makes music for pleasure, then reluctantly becomes a travelling business. While their music remained uncompromising, the external pressures and strains mounted. According to Sveinsson, their darker 2002 album ( ) – no titles, no lyrics – “really represents the state we were in at that time: this is so fucking heavy! Just keeping track of who you are is kind of tough.”

“You can easily lose yourself,” Hólm agrees. “You move around the world in this bubble called Sigur Rós. It is a bit of – excuse my French – a mindfuck, being in a band that young.” By the end of the 2000s, he says, “we all crashed a little bit. We just didn’t admit it to ourselves.”

Sveinsson had always been the most sceptical about “going into the industry and taking part in all that noise” and by 2012 the noise was too loud. “It was just too much. I was burned out and had to leave.” Did it feel like a temporary break? “No, it felt very final, actually.” His bandmates pressed on with the unusually crunchy and imposing Kveikur (2013). “Maybe it was some sort of retaliation,” says Hólm. “That album is quite aggressive and angry.”

“I call it the inferior album,” Sveinsson deadpans. “No, no, it’s great.”

The band appeared to be thriving, headlining arenas and appearing in The Simpsons and Game of Thrones, but sessions for a new album fizzled out in 2017, around the time Birgisson stealth-moved to LA for a change of scene. “Very sunny and bright compared to dark and depressing,” he says. Zoom-phobic and just out of bed, he angles his phone so that all I can see most of the time is a shrub festooned with Christmas lights. I feel like David Attenborough, scanning the undergrowth for a glimpse of the lesser spotted Jónsi.

Ironically, it was pesky admin that held Sigur Rós together when the music stopped. Sveinsson still needed to be consulted on reissue packages and approve sync requests. The working title for 2005’s explosively joyful single Hoppípolla was The Hit Song and that joke came to pass. It has supplied emotional uplift to everything from the BBC’s Planet Earth and the Children of Men trailer to the film Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. What did the band make of the movie’s take on Iceland?

“To some extent, it’s quite accurate,” Sveinsson says, “but to other extents, it’s total bullshit.”

“The cliches are funny because there’s a hint of truth to every cliche,” Hólm says.

The band’s relationship with Iceland is complicated. As the country’s most famous export after Björk, they were constantly asked about glaciers and elf magic. “Obviously us doing photoshoots all wearing the same hat, looking like elves, that didn’t help,” Hólm admits. “It did become slightly annoying, but there is this element of truth to it. The other day I was walking my dogs in the countryside and listening to the new record in my headphones and I thought, wow, this really does sound like what I’m looking at.”

The tax case put them at odds with their own country for the first time, to the extent that Hólm considered emigrating. How close did he come?

“I really did feel like I can’t live in this sort of society,” he says. “I felt violated, basically. It was a dark period of time for all of us. It was scarring, you know. But then you realise that things just happen and it doesn’t really matter where you are. I have come to the conclusion that I love living in Iceland.”

They blow hot and cold on the reasons for the second prosecution. One minute Hólm suggests equably that “it’s nobody’s fault really”, the next he wonders if the government was trying to make its most famous band “the poster boys of something”. Sveinsson suspects that Sigur Rós were “an easy target” compared to lawyered-up bankers and hedge-fund managers. Birgisson still sounds furious about “this fucking bullshit … The unfairness of it all, and the aggression. There’s so much energy and time that goes into it that could be spent on beautiful things. You get angry thinking about it.”

Distance has enabled him to romanticise his homeland in lyrics that he describes as “a postcard to Iceland”. He’s thinking of leaving LA. “America is so crazy,” he says. “Trans and queer and gay rights have been trampled on so much recently. It’s scary to see. Around the world also, it feels like we’re going backwards.” Átta’s artwork, by the veteran Icelandic artist Rúrí, depicts a rainbow flag in flames. “We try to stay out of politics, just to make the music as neutral as possible, but we were talking about the state of the world we live in now: climate change and doomscrolling. You see all the psychopaths spending crazy amounts of money going to space when they could be saving our planet we are actually living on at the moment. It’s so unbelievably ridiculous!”

Átta (Icelandic for eight) began life in 2018 when Sveinsson visited Birgisson as a friend and they started tentatively making new music together. “It felt like nothing had happened,” Sveinsson says. “It was like, ‘Oh, you’re back! There you are!’” The band felt wiser, and more comfortable with their personality differences. “We’ve all matured,” he says. “When we are together it’s the music. We don’t have to be best buds.” Hólm pulls a mock-offended face, then laughs.

Sigur Rós don’t talk much in the studio. The loss of a drummer and the return of the string arranger set the lush, contemplative tone. “We wanted it to be spacey and beautiful – a little bit pure somehow,” Birgisson says. “You’re getting older and more cynical and it’s harder to move you – you just want to feel something.” He likes silence, or a soundtrack so soft that it is neighbour to silence: vintage jazz and field recordings of nature. “I’ve always been a little bit of a music hater,” he confesses. “There’s not very much I like.”

When the new album’s slow advance was frozen by the pandemic, this self-defined “big loner” rather enjoyed lockdown, he says. “Because I’ve been living [out of] a suitcase for 20 years, being in the same place for two years was unheard of. So this, for me, was a beautiful rest.” He exhibited paintings and sculptures, released a clubby solo album (2020’s Shiver) and continued his study of perfumery. “With aroma molecules you have individual notes and tones, so you can focus your scent composition,” he says. “It’s a little bit like music: how the elements harmonise, how much space there should be. I love this idea of triggering senses in different ways.”

Could he see himself letting Sigur Rós go altogether? He thinks not. “You have more outlets but you always love the band. It’s been part of your DNA for so long, so you don’t want to kick it to the kerb. I love Sigur Rós and I love what we have created.”

By growing up, the band have somehow looped back to their adolescent origins, when making music was a choice rather than an obligation. “For me, when we’ve done this tour, that’s it; see you in a few years,” Sveinsson says, cheerfully. “I don’t care. I can’t foresee anything after this, but who knows?” Life, they have discovered, sometimes has other plans.

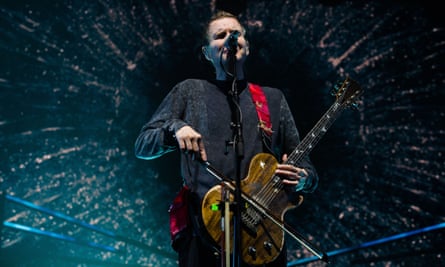

Átta is released on BMG/Krunk today. Sigur Rós perform tonight at Meltdown festival, Royal Festival Hall, London, in collaboration with London Contemporary Orchestra.