THE LAST GREAT ANALOG CAR WAS BUILT, in 107 examples, between 1992 and 1998. The roadgoing version had a world-first carbon-fiber frame; a 627-hp, 7500-rpm BMW V-12; a six-speed manual gearbox; and a driver’s seat mounted in the middle, aping an open—wheel race car. You did not get anti-lock or power brakes, traction control, power steering, or anything resembling an electronic safety net, despite the fact that the car cost nearly $1 million at launch. (Or that most of those features were standard on cars costing far less.) What you did get was the fastest production car in history—231 mph— and one of the least compromised road machines ever built.

None of that was by accident. From general layout to minor design touches, the McLaren F1 was dictated by the will of one remarkable engineer. And it came from a small, eminently focused company at the height of its power. By 1993, McLaren had won seven Formula 1 constructors’ championships and landed wins everywhere from Can-Am to the Indy 500. Gordon Murray, the F1’s chief designer, had come to McLaren after a stint at Brabham, where he drew two title-winning Formula 1 cars. In Woking, he co-designed the McLaren that gave Ayrton Senna his first F1 championship.

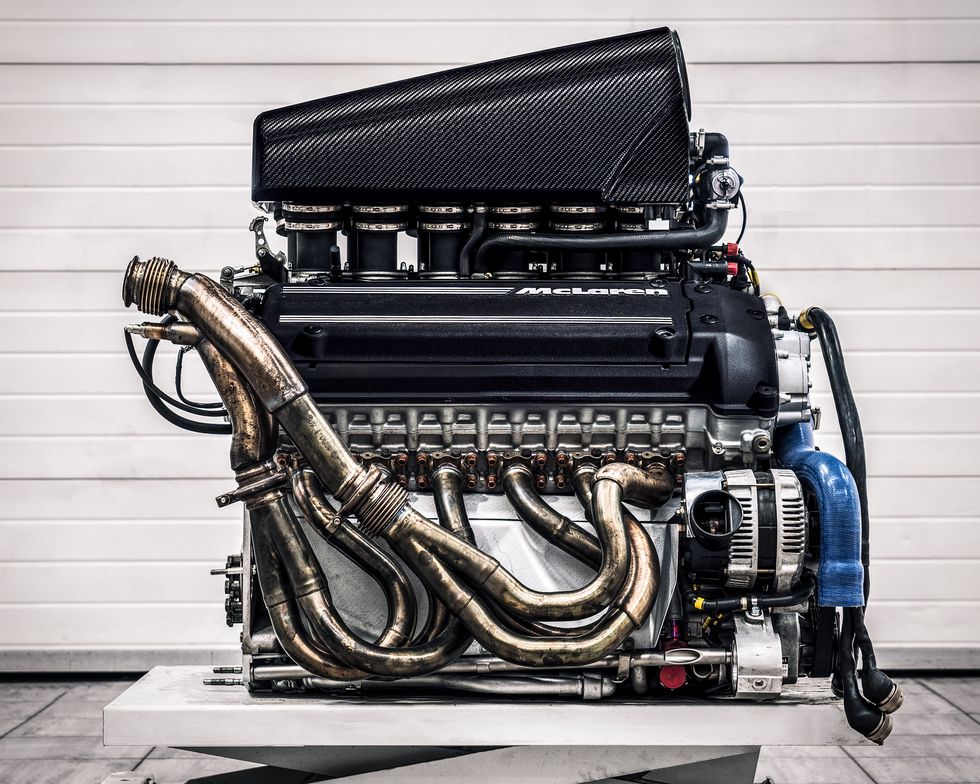

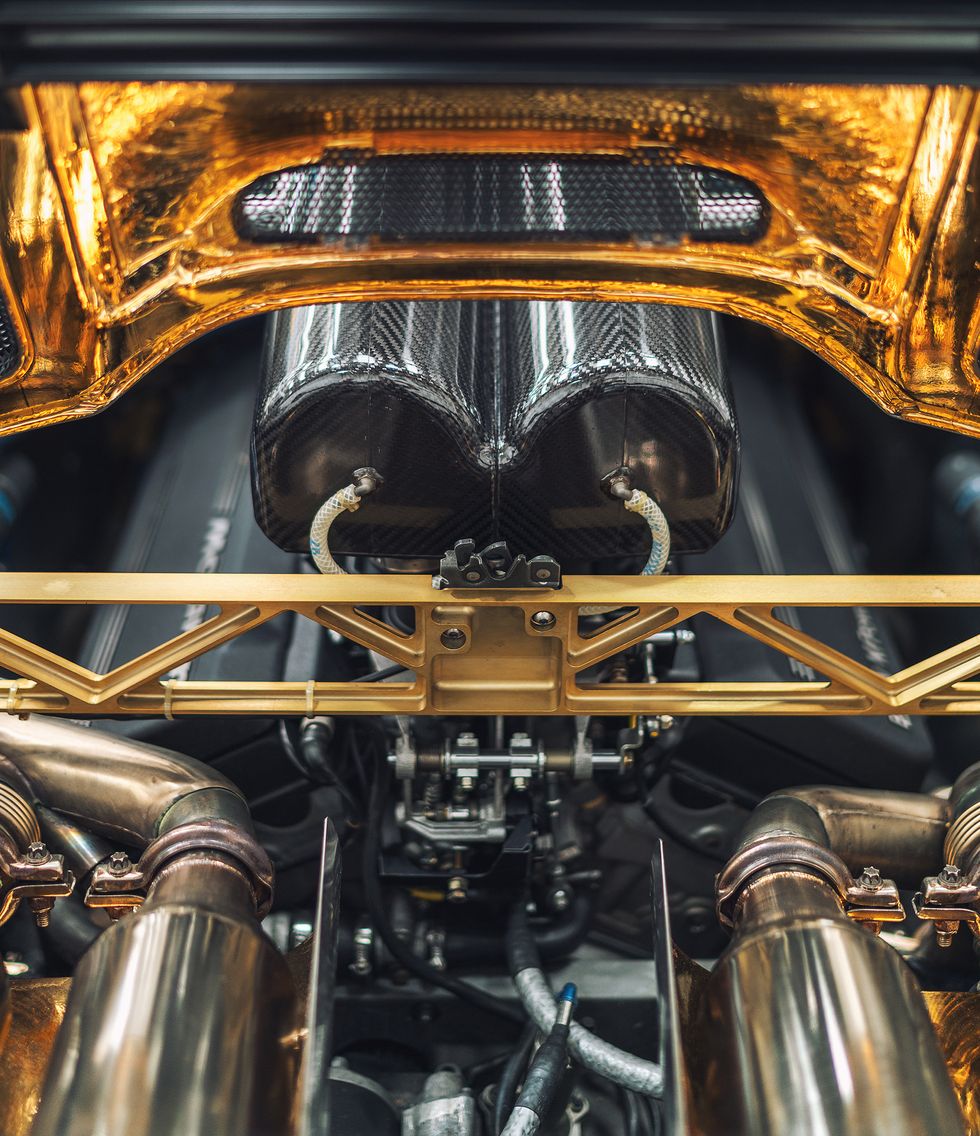

Neither Murray nor McLaren had ever built a road car, but the company gave him carte blanche. He got whatever he wanted, from an engine cover lined with real gold foil to that landmark V-12. The latter was the work of BMW Motorsport’s Paul Rosche, the genius behind the German company’s 1000-plus-hp, championship-winning Formula 1 four-cylinder. Along with a small team of engineers, Rosche built the F1’s engine in just nine months, after McLaren partner Honda got cold feet.

The car weighed 2425 pounds dry. It came with a built-in 14.4k modem for sending diagnostic information to the factory, at a time when most of America didn’t have an Internet connection. McLaren famously flew mechanics around the world to service it. Murray had never wanted to take the car racing, but customer demand prompted the creation of the F1 GTR, essentially a production F1 with a roll cage. FIA rules left the model 27 hp down on its roadgoing sister, but it won Le Mans anyway. And pretty much everything else they threw at it.

The F1 was unveiled to the public 25 years ago, in May of 1992. Astonishingly, every supercar since has been something of a dilution. The Bugatti Veyron is faster but more complicated and distant. Porsche’s iconic Carrera GT is a decade newer but slower to 60 mph and more difficult to drive. Even McLaren’s own 903-hp P1 hybrid, which just left production, is 14 mph slower and a third of a ton heavier.

The F1’s origins have been covered to death, but we wanted to illuminate the thing’s life past the factory gates. To lift the veil and take a look at the living, breathing car underneath. Because above all, that’s what Murray wanted to create—not the museum piece or investment that his work has become.

We spoke with owners, racing drivers, and various lights in the car’s orbit, and we found a story that still holds lessons. And a reminder that, while the world may now be faster and smarter, a quarter century later, there’s still only one F1.

LIVING WITH IT

JAY LENO (Owner): Well, I’ve had mine almost 20 years. When the car came out, there were so many other supercars just coming out—Vector [W8], [Jaguar] XJ220, Bugatti EB 110. The Jaguar was the most expensive. Six-hundred-thousand-dollar range. And all of a sudden, you had this car that was close to a million dollars.

How much better could the million-dollar one be? Is it really three or four times better than a Lamborghini or Ferrari? And of course it was, but nobody knew it at the time.

CHARLES NEARBURG (Owner): If you blindfolded somebody and put them in it, they would be hard-pressed to tell you it wasn’t made yesterday.

ROGER CHATFIELD (Composites technician, McLaren): When the company was that much smaller, they arranged for the whole factory . . . every person could have a run at one. For me, [McLaren director] Creighton Brown was driving. He said, “We’re going to start by demonstrating its torque ability.” Basically, he just put it in gear, didn’t touch the throttle. The car started moving away. Next gear, car moving away, still no throttle. We’re just going up through the gears with no throttle. It’s like, this is bogus. This shouldn’t be working.

NEARBURG: It’s actually sprung quite softly. Much more body roll than a “modern” supercar. You realize Gordon knew what he was doing. He built a package that generates extraordinarily high g’s, but it’s very comfy. He didn’t have to rely on superstiff springs and superbig roll bars to get it to work.

MARK GRAIN (Senior technician, McLaren Cars/Motorsport): There was a German customer, a businessman. He lived in Cologne, commuted in the car every day. He said, “Oh, I’ve got a problem, this warning light. I’ve looked in the manual, can’t find anything. Can you send somebody out, see what it is?”

So one of the guys went. It turns out it was the engine cover lifting slightly. The warning light for the engine cover.

But the only time the car ever did it was 185, 190 mph. “It does it on the way to work, and it does it on the way back.” Every day.

LENO: It makes the greatest noise ever. And there’s no flywheel—you turn the key off, it stops right now. You don’t get that half a second of rrr. The only analogy I can make: One time I did a concert with Paul Simon and Paul McCartney. There wasn’t a guitar strum, a string—the song ended right now.

NEARBURG: You can tell by the way it responds. You just feel the lightness immediately. It’s a joy to drive, a very honest car. Sitting in the middle isn’t disorienting, and the only thing that’s complicated is paying tolls in a foreign country. When you have half of Italy behind you, standing on their horn, when you’re trying to figure out how to get the toll in the damn booth.

LENO: That’s the real key to the car: It’s incredibly light. The nose does get a little light at extremely high speed. It’s not as planted as, like, a P1, but then, it’s 20 years earlier. Being carbon fiber, you have the occasional clunk—you hit a road marker, you feel it ripple through the chassis. You drive a new NSX, and that’s like a solid billet. You realize the car weighs the same as a Miata?

RAY BELLM (Racing driver): I have a contract to [run the McLaren F1 Owners Club], because I went to Ron [Dennis, McLaren’s then chairman] in 2011. I said, “Ron, these cars, they’re all sitting there doing nothing. No one uses them.” Anyone who has a car is a member, just by the fact that they’ve got a car, and we run tours and do probably 700 or 800 kilometers over three days. But the result has been that, in 2011, the cars were worth about $3 million, and they’re now $15 million. Rich people always want to do something no one else can. So the entry ticket is a McLaren F1.

HENRY WINKWORTH-SMITH (McLaren Special Operations Heritage Manager): There are more cars being used now than when I started 10 years ago. People have suddenly gone, “Actually, I can’t get this experience in anything else.” And because the values have climbed, people haven’t been quite so worried about increasing mileage.

LENO: It’s funny, because everybody talks about no ABS, no stability control, no traction control. Yeah, like an MG! Or a Triumph from the Sixties. And it will get away from you—you go 70 and downshift into third and nail it, that rear end’s gonna break loose, unless there’s heat in those tires. It’s a bit like a loaded gun—you have to know how to handle it, all the time. Not like cars now.

CHATFIELD: [Passenger seats on] either side of the airbox, driver in front. It’s just like a wild dog barking at you, every time he’s going through the gears.

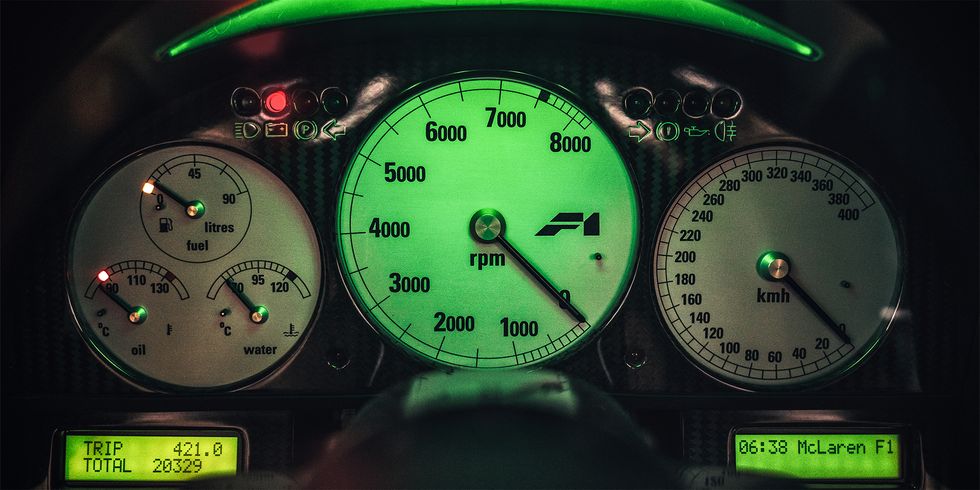

LENO: The needle moves so quickly, your eye can’t follow it. Because if you’re looking at it, you’re already in jail.

FIXING IT

JOHN MEYER (Senior technician, BMW of North America): It’s like any good sports car: If you don’t drive it hard, it’s not gonna like it. There were a lot of guys who really thrashed their cars and didn’t really have problems.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: Paul Rosche, rest his soul, said, “This engine should be designed, developed, like any other BMW series engine. It should not need an opening for 250,000 kilometers.”

LENO: Talk about getting something right the first time! There are a number of them that have [huge] miles. I’ve never known anybody to have any trouble with it.

BILL AUBERLEN (Factory racing driver, BMW): The GTR had sequential shifting, right? Every sequential I’ve ever been in is pull to shift up. Gordon’s idea was that you’re stronger when seated, so the GTR was push to shift up. Three in the morning at Le Mans, you’re almost asleep in the car, and all of a sudden—you shift the wrong way.

Luckily, the engine is bulletproof. There are stories about where a water hose fell off and they drove it all the way [back to the pits]. It’s melting everything around it, and it makes it.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: The race engines were designed to do 9000 kilometers between big servicing. We had one road engine that the customer decided to send his car to a nontrained servicing place. They used the wrong oil—we found a lot of wear. It’d been foaming up and not pumping around the engine properly. And they tightened up what they thought was a chain tensioner. That put too much tension on the timing-chain assembly—one of the bolts loosened and started smashing up and down underneath the pistons.

So we had that engine back. It went back to BMW Motorsport, got stripped and rebuilt, even re-Nikasil’d. And it’s a good story, but that’s the only time I’ve heard of it happening.

MATT FARAH (Journalist): My favorite McLaren F1 story is from Ralph [Lauren, a family friend]. About the year 2000. One of his three F1s. The car wasn’t running right, so he plugs it into the wall. The car dials McLaren. Two guys in tweed jackets come over from England, they show up at his house. They go, “Okay, give us the keys.” They come back and go, “You’re not shifting high enough,” and fly back to England. That was it, the whole problem. That’s what owning a McLaren F1 is like.

LENO: You forget—there weren’t even [smartphones] when this came out. It just seemed so improbable.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: Until three months ago, we were using those [original 1990s] laptops [for diagnostics]. Our technicians were being stopped in airports and asked to prove that it was a real laptop, because [security] thought it was a bomb. They were like, “No one uses those laptops anymore.”

MEYER: It runs on a DOS program!

WINKWORTH-SMITH: There was a Jalopnik post, someone took a picture of a laptop here. First off, our workshop manager was furious, because there was a car up in the background and it didn’t look all smart and neat. But that article was hilarious, because I probably got 45 or 50 emails offering me laptops. Ranged from, “I have one of these laptops. I’m not using it. I would like nothing more than the thought of that laptop looking after a McLaren F1. Please give me your address, and I will ship it,” to some guy who was like, “Well, if you haven’t got them, I’ve got one. I want $20,000.”

LENO: We do our own servicing on the car—as advanced as it was in the day, it’s nothing compared to now. What’s funniest is that the car comes with a tool roll. The most beautiful tool set you’ve ever seen. Titanium wrenches that weigh mere ounces. The idea that, if your McLaren breaks down on the 101, you’re going to get out the tool roll and fix it.

MEYER: Because the cars are driven very infrequently, servicing is by time. Every nine months was a basic service. Eighteen months was a major service. Every five years, the fuel cell has to be replaced.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: It’s an FIA-spec bag tank, which is brilliant for crash regulations, but . . .

MEYER: The whole back of the car comes off.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: About 25 or 30 hours? It’s easy, but it takes a long time. It’s not that everything is accessible. So the fuel tank, it’s engine-out. Water-temperature sensor, it’s engine-out.

But because you’ve taken the engine out, you need to do a suspension setup. And they’re hand-built; they’re not all the same. One car might set up really easy, and the other might be really difficult. To get all the ride heights and cross weights and everything dialed in, it could take a day. You just don’t know.

LENO: There are no parts. When you break one, they will make you the part. But there’s not a lot of off-the-shelf stuff.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: We’ve got very few windscreens left, for instance. They have this special coating between the two laminates, which means you don’t have wires in them, which gives you a heated windscreen.

To be British, they’re jolly expensive. And, you know, you could put a cheaper GTR screen in, but the voltage is different, you haven’t got your wiring, and it hasn’t got the same blue tint. So we said, Okay, the only way we could do it is to invest in [ordering a complete glass set]. It’s hundreds of thousands of pounds. But it’s important to do it, to keep these cars on the roads.

LENO: When I first got it to the dealer for service, they said, “Oh, replace the wiper blade.” I said, “Well, I don’t drive the car in the rain.” They said, “It’s part of the service.” I said, “How much is the wiper blade?” They said, “$1500.” I said, “You know what, don’t replace the wiper blade! I won’t take it out if it rains.”

You’re at the point now where anything on the car . . . it’s a house.

MEYER: At one time, we had four in the shop at once. [BMW], back in New Jersey, was having a heart attack.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: I mean, insurance, kill me. We have this limit of two [in the shop at a time]. We had 14 in here at one point. I got a big telling off for insurance. I think the [extra] cost to us was substantial.

LENO: It’s still a car. It’s still a 20th-century automobile in the sense that you see where everything is. We broke a shifter fork on it; we made a new one. It’s just a shifter fork. It’s aluminum. It’s not that unusual. That’s the funny thing about it. All these cars have taken on this mythical status, but they’re still cars. More cleverly put together than most, by a long shot, but it’s still a car.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: Whenever we service a car, there will be two road tests carried out. So we truck it to a test track, and we’ll do a seven-page test procedure, test every single thing on the car. And that goes from pulling the handbrake at 50 mph to see what the retardation’s like, to full-throttle accelerations, to really heavy braking to see what the balance is like, to rating the stereo performance at mid and high volume on a scale of one to ten.

GRAIN: One of the F1 road cars was on display at some event. The engine cover, it’s all gold foil. We’d nicked it from aerospace. [A bystander said,] “You’re doing it just because it’s a shiny color and it’s expensive, and it allows you to bill more for the car.” And a colleague replied, “It is the lightest heat-effective material we can use in that application.” Everything was there for a reason.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: Over time, [the foil] degrades. People touch it, they try and clean it, it rubs off. That’s why we replace it. It’s not actually that mental. It’s a few thousand pounds.

LENO: It’s just so beautifully put together, and so simply. It’s not meant to be complicated, it’s just different.

MAURIZIO ZAGARELLA (Technician, McLaren): We were called flight doctors. Anybody used to fly anywhere if there were any issues.

NEARBURG: Pani Tsouris has driven more miles and knows more about these cars than anybody alive, with the exception, I guess, of Gordon.

PANI TSOURIS (Traveling F1 technician, McLaren Special Operations): I just came back from the United States. A clutch in Minnesota and a fuel-tank replacement in Florida.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: Twenty-four/seven, both of us. I switch my phone off Christmas Day, my anniversary with my girlfriend, and her birthday. Pani’s test-driven cars at midnight.

TSOURIS: Nothing [I do] is an emergency, in terms of fly out tomorrow.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: I think the shortest trip—a guy in Europe got a flat tire. Within an hour and a half, there was a technician at Heathrow, with a wheel in his luggage, flying to the nearest city, who then got a taxi to this car on the side of the road. Three and a half hours later, he was there.

TSOURIS: [For jobs requiring] more than two and a half weeks of work, it’s in our best interests to bring the car back. Or try to, at least.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: These days, because of the value of the car, it’s almost impossible to write one off.

A good example is—if you do a bit of Googling, you’ll find out who I’m talking about. His car came in, and he’d had a fairly substantial shunt. The car was in two halves. It had split. The car had done brilliantly, because he’d hit it right in the middle. The passenger [cell] was absolutely perfect. We cut all the damage out of the tub, x-rayed it, crack-tested it, and then, using all the original body molds, the tooling, the layup books, and also some of the original staff that built these tubs back in the day, we rebuilt it.

DANNY ENGLAND (Composites technician, McLaren): We are, of course, the only company in the world that is physically capable of rebuilding F1s.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: And now that car is driving around, as good as it left the factory, even down to doing torsional-rigidity tests. And to do that, we had to measure it against another F1. So we stripped two other cars down to make sure it was gonna be the same.

PHIL HARDING (Development technician, McLaren): It’s not like you can go and pick another monocoque out and build a new car. It’s cost-effective to repair something worth 5 million pounds, isn’t it?

RACING IT

BELLM: The project was born as a conversation between myself and Ron Dennis. I ordered a road car, chassis 046, in 1993. I said to Ron—who I’ve known for many years—“I’m going to race it.” He said, “Oh, don’t do that, ’cause it will cause me so many problems. If you want to race the car, I’ll build you one for a million pounds.”

In retrospect, I should have said yes. I said, “Oh, I can’t afford a million pounds for a race car.” He said, “Find two other customers, and we’ll make three.” I said, “This car will beat everything out there.”

MARK ROBERTS (Designer, McLaren): Gordon mentioned to me once that he almost felt pressured into it. It was never designed as a race car.

HARDING: I think the idea was, we’d just do one to see how it goes. All we did, basically, was the minimum to get away with, to meet, FIA regulations. Air jacks on it, roll cage in, bag tanks, and a little bit of solder work.

ROBERTS: If we didn’t do it properly, people would go out and do it anyway. It was considered the right thing to do.

AUBERLEN: 1998, I drove a Longtail at Le Mans. When you release that speed-limiter button on hot tires, I swear to God: I was better-looking, I was taller, I felt better about myself. It’s a car that has a spirit and a soul. You’re going down the Mulsanne at 200 mph. You could see the wheels light up from the carbon brakes, the flames coming out the back.

BELLM: The first year, ’95, was just a stripped-out road car. The steering was so heavy, you could barely hold it around corners. So the first thing we did [was ask] for a new steering rack. And to this day, the steering rack of the GTR is infinitely superior to [that] of the road car.

AUBERLEN: When it first came out, it was at the top of the field, so you didn’t have to drive 20 percent over the limit all the time to try to keep up. I mean, there were times when we were probably 30 seconds ahead of the field. You’re not even racing at that point.

BELLM: When we first tested it, it was quite a handful, because Gordon Murray didn’t believe in rear anti-roll bars. It had no rear anti-roll bar—he thought you could control it all from the front. And because you had so much torque, we had to work quite hard on getting decent traction. But basically the engine was so far and away better than everything else [we raced]—F40s and Porsches, Venturis, all sorts of rubbish. Only in ’97, when Porsche and Mercedes woke up, did we start to have what I would call naked competition.

AUBERLEN: It’s always there. It’s a very stiff, rigid carbon tub, and [the Long-tail] has reasonable downforce, so it’s a very stiff car. You notice that right away. It’s very consistent on the tires.

BELLM: It’s satisfyingly demanding if you know what you’re doing. Frighteningly demanding if you don’t know what you’re doing. Which is why there have been one or two accidents. In the wet— people don’t realize this, but at Le Mans in ’95, the car ran with zero downforce. It actually had lift at speed.

AUBERLEN: I know so many people that, once they get comfortable, they’re like, [makes crashing noise]. It doesn’t give you a lot of feedback. It’s great, great, great, right up until biting you. That window of the unknown—it takes a while to get used to that.

ROBERTS: During ’95, ’96, and ’97, we were producing monthly or fortnightly updates for the cars. It was a typical Formula 1 attitude. We were just trying all the time to improve the car.

AUBERLEN: You gotta wait a minute for the grip to come up on the tires. It will not give it to you in a lap or two. And once there, you sort of just flow with the thing. There’s no sliding. With the GT cars that we race now, you’re always moving something around.

BELLM: I don’t want to upset Gordon, ’cause he’s a friend of mine, but I always say it’s the most wonderful engine in a compromised chassis. The engine was sublime. It wasn’t designed as a race car, so all the angles were wrong on the suspension. You couldn’t get the car low enough, and if it dropped too low, it locked out. The ’96 car—which is why a lot of us bought ’96 cars—they changed some of the geometry, so we could get better grip. But I think other than one car, we all fitted rear anti-roll bars. Gordon was absolutely shocked.

JAMIE LEWIS (Electrical engineer, McLaren): It was a very small team. The scale now is such that you have to have business processes and systems, so a lot of the time, you feel a little bit removed from the core. It’s a much bigger operation. You just can’t work that way anymore.

GRAIN: I always remember looking at the grand-prix team, and just thinking, They’re a bunch of bastards, they are. . . they do it right. There was always an air of confidence tinged with a bit of arrogance: “Even if we’re not absolutely the best by winning races, in the garage, we were bollocks. Everything will be in place. Everything will be spot-on.”

LOOKING BACK

LEWIS: Normally, you start a company, build a product. McLaren Automotive exists today because of that car. It was designed to build a company.

ROBERTS: None of us had any idea of how legendary it was going to become.

ANDY WELLS (Parts manager, McLaren): I didn’t actually appreciate it until now, to tell you the truth. We won Le Mans with pretty much a road car. It’s the biggest thing I’ve ever achieved in my life.

ENGLAND: A bunch of people, all from the motor-racing industry, had no idea about road cars. But that’s the bit that made it fun and exciting.

BELLM: The P1, you can drive the rocks off it, and you feel completely at home and in control, because the grip levels and the electronic-traction levels, and the brake-steer help you a lot. But turn it all off, it’s a bit like driving an old F1.

AUBERLEN: I probably drive [BMW of North America’s exhibition F1 GTR] three times a year. I take people for rides, and it blows their minds. The downforce on our modern-day GT cars is way higher. When you’re skating around low-downforce, it’s pinkies up, very dainty on the steering wheel. This car is still way faster in a straight line—it will just destroy [new] cars. And listening to that motor. I mean, the restrictor’s right above your head.

LENO: Right now, it’s kind of like champagne. It’s something you have once a month or on special occasions.

MEYER: If you think about when it was designed and built, everything on that thing was Formula 1. They were not saving any money on anything at all.

I loved it. I miss them terribly.

ROBERTS: Gordon said, “Just go and see what everyone else is doing, and make sure you do something significantly better.” So I managed to get hold of an F40 owner’s manual and a 959 Porsche manual. . . . The whole ethos was craftsmanship and that human element, so I thought we should hand-draw the manual. Pencil sketches and watercolor. Nobody would ever be crazy enough to sort of do that sort of thing again.

BELLM: I love the car and what it stands for. It was a massive step forward, basically the Ferrari 250 GTO of the Nineties. We just don’t realize how far technology has moved. The gearbox, which was not the easiest. The porpoising at speed, which meant it steered itself. The car tracked a bit, because of the lack of camber and caster. Lots of little aspects that just made the car, made you concentrate.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: They’re just so . . . different to modern cars.

ROBERTS: We still refer back to them almost on a daily basis. The purity in the design. The package.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: If you look at what other cars in the market are doing—250 GTO at whatever they’re worth these days, 50 [million dollars] or whatever, the general thought is that the F1 is the next one of those.

BELLM: In 2004, I bought probably the cheapest-ever F1. I paid £300,000 on chassis 016R. I sold it for £650,000 and thought I had made a complete and utter killing.

WINKWORTH-SMITH: These days, 13 to 15 million for a road car. Apart from the car we own—GTR 01R, the Le Mans winner, we’ve had some very silly offers—a really impeccable-history race car would be 20, 22 million restored.

AMANDA MCLAREN (McLaren ambassador, daughter of company founder): They arranged for me to be taken for a drive [in a roadgoing F1]. Down this residential road, all the curtains are twitching. There was a bulbous lorry in front of us . . . bits start falling off . . . this guy starts sweating. He starts telling me how much the insurance is. More than my house was worth at the time.

NEARBURG: I was told by the staff of the Petersen [museum] that of all the cars in their Precious Metal exhibit, the F1 probably attracted the most attention. And without a doubt among anybody less than 40 years old. When you drive it, it’s almost unnerving. People either recognizing it, or not immediately seeing the driver and freaking out.

BELLM: It’s unbelievable. It’s just pure adulation. People recognize it because it’s the iconic car of the Nineties, the first of the all-carbon, the real supercars after the F40, which was a space frame covered in bits of plastic.

LEWIS: I started in ’91 . . . probably about 120 people in McLaren Cars. And now it’s 3500. The scale of the operation has changed so dramatically that it’s almost incomparable. But there’s still that sort of core DNA that exists, that Ron kind of instilled in all of us. Attention to detail and doing things right.

ROBERTS: Obsessive-compulsive disorders. We all suffer from that.

And if you don’t, when you join the company—you will. We’re lifers. It gets under your skin.

LEWIS: That no-compromise thing.

ROBERTS: Remember, Gordon and the original team were mostly race people. They lived in that world already.

NEARBURG: He’s incredibly hard-working. Never stops thinking, never stops doodling, never stops pursuing his passion for how to improve automotive manufacturing. His whole new thing that he’s got going on now—building trucks in a box for the third world that can be assembled in a few hours with common hand tools. He’s still got such a fertile imagination.

ZAGARELLA: We were all looked after by the business. Even our families. I think that’s what made this company great. I think it came from Ron and Gordon, who were very much the same.

NEARBURG: One of the most hilarious things is watching [Gordon] drive his little Bugeye Sprite. He throws on this little leather bucket helmet, and he plops in that thing, and he goes ripping around like he’s on the Isle of Man or something. But he’s still a very intense, focused, driven guy. My sense is that he’s doing this stuff because he wants to make a difference.

GRAIN: At heart, he was a racer, wasn’t he? Still is.

NEARBURG: How often in this world does one guy—one guy who is supremely qualified and has all the resources that he needs—how often does that guy get to design the ultimate anything?

Sam Smith is a freelance journalist and former executive editor at Road & Track. His writing has appeared in Esquire and the New York Times, and he once drove a Japanese Dajiban around a track at speed while being purposely deafened by a recording of Taylor Swift's "Shake It Off." He lives in Tennessee with his family, a small collection of misfit vehicles, and a spaniel who is scared of squirrels.