Mount St. Helens Still Highly Dangerous, 30 Years Later

Washington State mountain ranked second biggest U.S. volcanic threat.

Thirty years after Mount St. Helens blew its top, the peak is still the second most dangerous volcano in the United States, according to government estimates. (Pictures: America's Ten Most Dangerous Volcanoes.)

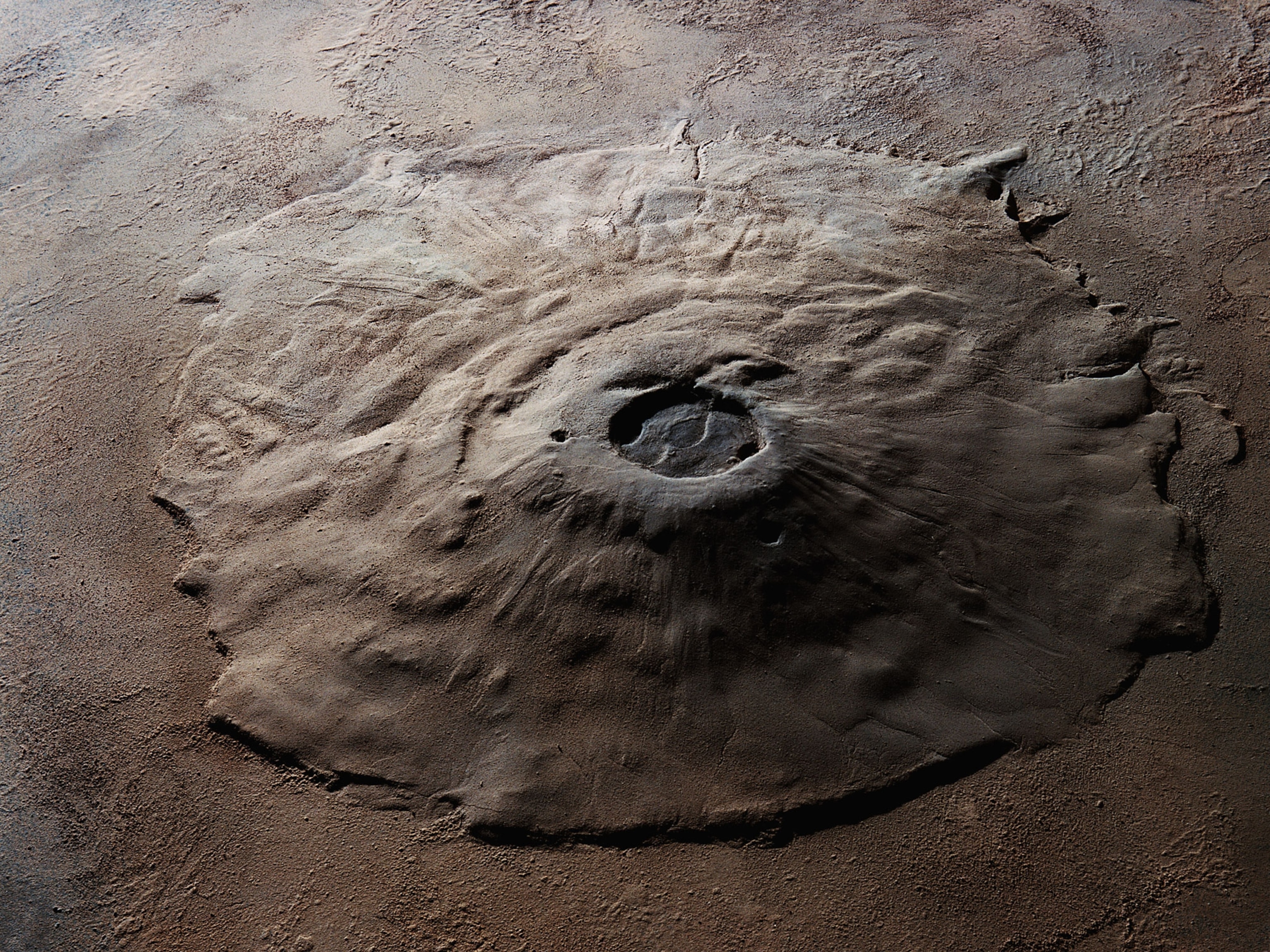

That's because the Washington State volcano poses a triple threat: Mount St. Helens is one of the most active U.S. volcanoes, its eruptions are highly explosive, and it's situated near major metropolitan centers in the Pacific Northwest (see map), said John Ewert of the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) Volcano Disaster Assistance Program. (See Mount St. Helens pictures in National Geographic magazine.)

The U.S.—the most volcanically active country after Russia—has 169 volcanoes that the USGS and other agencies regularly monitor. These volcanoes are rated based on eruption frequency and the risks posed to nearby populations, infrastructure, and air traffic, among other factors.

Eighteen of the U.S. volcanoes on the list are deemed "very high threat," with only Hawaii's Kilauea volcano surpassing Mount St. Helens, according to the latest USGS report, released in 2005.

The agency will likely update the most dangerous volcano rankings by 2012, and Ewert thinks Mount St. Helen's status will probably remain the same. (See pictures of Alaska's Redoubt Volcano—the ninth most dangerous in the U.S.—erupting in 2009.)

Although the May 18, 1980, eruption and resulting landslide destroyed much of the volcano's summit area, Mount St. Helens still stands 8,364 feet (2,549 meters) above sea level.

If Mount St. Helens reawakened violently, an ash plume reaching 30,000 feet (about 9,100 meters) or more could materialize in as little as five minutes, grounding aircraft and wreaking havoc on agriculture, water and power supplies, and human health, Ewert said.

Glaciers atop the mountain could also melt and carry volcanic debris down the valley.

For nearby communities—including Seattle and Portland, Oregon—the layers of volcanic ash settling out of the sky would be "just pretty darn unpleasant," he added. "Imagine someone dumping an inch of talcum powder on your house."

Mount St. Helens a "Sneaky" Volcano

Still, Mount St. Helens's 1980 eruption—which killed 57 and flattened more than 200 square miles (518 square kilometers) of forest—"really launched modern volcanology in a lot of ways. That's one of its lasting legacies," Ewert added.

For instance, the blast prompted many volcanologists to pursue better technologies for tracking volcanoes, both in the U.S. and worldwide, he said. (Explore an interactive showing how the Mount St. Helens' blast zone has changed in 30 years.)

"Probably the most important lesson" from Mount St. Helens is that volcanoes can rumble back to life and erupt in short periods of time, he said.

"These volcanoes—at the risk of anthropomorphizing a little bit—can be kind of sneaky."

Mount St. Helens gave just seven days of warning when it erupted again in 2004, and Alaska's Okmok volcano (which is not on the "very high threat" list) gave an hour's notice before spewing ash 50,000 feet (15,240 meters) high in 2008.

"When you consider you can have a volcanic reawakening and move into dangerous eruptions in a few weeks, if you don't have your act together and have instruments in place ... you're literally flying blind," Ewert said.

"With so many people and infrastructure at stake, we felt like that was a roulette game we're uncomfortable with as scientists."

That's why several U.S. volcano observatories support a National Volcano Early Warning System, which is now working its way through Congress. If put in place, the national network would ensure that the most dangerous U.S. volcanoes are being monitored, for example with seismographs and sensors installed on their flanks.

Right now only about a hundred of the 1,545 known active volcanoes worldwide are outfitted with monitoring equipment, noted Rick Wunderman of the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program in Washington, D.C.

Despite an ongoing "revolution" in monitoring volcanoes, the progress in predicting eruptions is still "surprisingly slow," said Wunderman, who worked at the Cascades Volcano Observatory near Mount St. Helens not long after its 1980 eruption.

Mount Rainier Volcano Also One to Watch

While Mount St. Helens gets its share of attention, Wunderman added that another Washington State volcano is also one to watch—Mount Rainier, the third most dangerous volcano on the 2005 USGS list.

"The point is that [Mount Rainier] doesn't even have to erupt," he said. "It's so big, so tall, and has so much ice that an earthquake or landslide" could combine with the region's heavy rainfall to send floodwaters gushing into valley communities built on an ancient floodplain below.

"It's a much more bleak picture than St. Helens in the sense of runoff—that's one thing that's on people's minds."

Overall, Wunderman compared Mount St. Helens' 1980 eruption with the recent explosions of Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which have disrupted global air travel for weeks. (See pictures of the Eyjafjallajökull ash plume.)

"Every now and then galvanizing eruptions occur. It isn't often that they're so big or anything of that sort, it's more the media and the consciousness of people who are taxpayers, or stuck people in an airport," he said.

"So it was [with] St. Helens, which went eight hours straight at full throttle ... and rained down over a vast area of the West—it woke people up."

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks