In the December 2017 issue of Aviation News, in the first of a two part feature, Major General Greg Feest (Ret) described joining the secret F-117A programme and the mission on which he dropped the first bomb of the Gulf War

It was the early morning of January 17, 1991. I had just turned on the Master Arm Switch of my F-117 stealth fighter in order to drop a 2,000lb laser-guided GBU-27 on an Intercept Operations Centre hidden in a bunker in Iraq. How did I get here?

Switching to a new aircraft

In the summer of 1987, I had just walked back into the 27th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) at Langley Air Force Base (AFB). I had returned from flying in a four ship of F-15Cs against a four ship of F-14s from Naval Air Station Oceana. I was still pumped up after our debrief when my Squadron Commander called me into his office. He told me I was being offered a position to go to Nellis AFB to fly with the 4450th Tactical Group. I knew that they flew the A-7D Corsair and that most of their flying occurred at night. Other than that, there was little information on their mission. I drove over to the Personnel Section at Headquarters Tactical Air Command to visit with the “Fighter Porch” guys. They gave out the assignments to fighter pilots. I knew a Major in the section so I asked him about the 4450th. He immediately told me he was moving to Las Vegas to fly with them in a month. This was all I needed to know. Since the “Porch” fighter pilots give themselves the best assignments available, I knew it would be a great assignment.

He also told me that I would need to meet several requirements to receive the assignment. I needed to be an experienced fighter pilot with over 1,000 hours of flying time and I needed to be an Instructor Pilot in a fighter. As an experienced Instructor Pilot, Flight Examiner and Flight Commander in the 27th, I met both requirements. However, he said that they recently added another requisite. The 4450th had lost two pilots due to spatial disorientation while flying at night during their bombing runs. Both of these pilots flew previous aircraft with only air-to-air missions. Therefore, they did not have any prior experience employing bombs at night. For this reason, the 4450th Tactical Group Commander had recently added the requirement that all future candidates must have bomb-dropping experience from a fighter. I immediately told him that I had dropped bombs off the F-111 as a Weapon Systems Operator but he told me that would not count since I wasn’t a pilot at the time. I then told him I had dropped bombs off of the F-15C when we spent a year checking out the bombing system of the F-15C Model. He said that was acceptable. Two months later I was off to Nellis AFB.

Entering the Black World

On arrival, I went to the squadron to meet my Squadron Commander and my fellow pilots. I was given a short introduction and briefing, which did not include any information about the F-117. Several days later, I found myself driving to Tucson to check out in the A-7 with the Arizona Air National Guard’s 162nd Fighter Wing, which was responsible for training all guard pilots in the A-7.

My checkout in the A-7 took two months and, after completing my checkride, I headed back to Nellis. It was after returning to Nellis I learned the A-7 was just a cover story.

I was taken into a secure briefing room and was finally shown the aircraft I would be flying – the Lockheed F-117A Nighthawk. I needed some convincing that it could actually fly. After a short video, I realised it was a real aircraft and went from there. Three months later, I flew the stealth fighter for the first time. I flew solo, since there are no two-seat F-117s. It’s just you and the aircraft. It was inspiring.

After my first flight I was given my ‘Bandit number’ – 261. Each F-117A Nighthawk pilot was given a sequential number in line with when they first flew the aircraft.

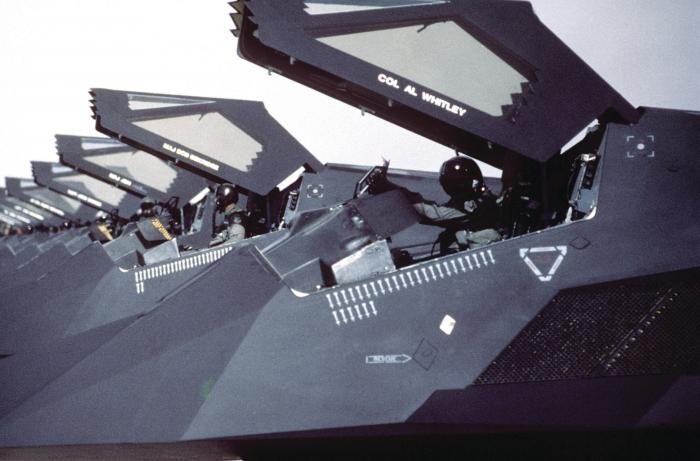

One advantage of the F-117 cockpit was its avionics. Most of it came from other aircraft and was familiar to the pilots. The engineers, after speaking with fighter pilots, put the displays and control boxes in the right place, making it easy for the pilot to operate. We had a head-up display (HUD) and the radios were in the right place. It was a good-sized cockpit, much like the F-15 with lots of space on both sides.

You can stretch your legs and lift yourself off the seat. It’s very comfortable, especially on long flights. Everything was accessible with no need to reach down or behind.

The view from the F-117 cockpit was different. The view to the rear was non-existent, but we never planned to have anyone behind us! Visibility during the day was good, but at night any flashing lights reflected off the flat panels and that was a little disorienting, but you got used to it. Noise level in the cockpit was low. As your speed increased there was little change in the cockpit noise. You could actually accelerate without knowing it. It was that quiet.

The stealth fighter carried two, 2,000lb [907kg] bombs inside an internal weapons bay. Our primary weapon was the GBU-27, a modified GBU-24 designed specifically for the F-117. It was a laser-guided bomb with bunker-buster capabilities against hard targets. We found that the GBU-27 rarely had any failures and usually guided exactly where we aimed it. We would illuminate a target with a laser designator located inside our aircraft. The only condition for employing the GBU-27 was the maximum altitude. We had to fly below 10,000ft over the ground in order to employ the weapon. This became an issue for us later in Operation Desert Storm.

The F-117 was not a demanding aircraft to fly. Keeping the infrared cursors on the target while everyone was shooting at you was a challenge. We were well trained and, going into combat, our goal was to fly right over the target, drop a laser-guided bomb and get out. We couldn’t launch and leave, but had to fly right into the threat. Our biggest initial concern was with the stealth technology. We didn’t know if it was going to work. It obviously did, but those first few Desert Storm sorties were a little nerve-racking.

The F-117 was not built for aggressive manoeuvring like the F-22 or F-35. It didn’t have afterburners and was strictly a subsonic aircraft. Our job was to limit any excessive manoeuvring, because any time you turned the aircraft, it changed the radar cross-section.

Life at Tonopah

From its inception in the late 1970s, until it was publicly acknowledged in November 1988, only the personnel directly involved with the programme knew of the very existence of the F-117. It was considered a ‘Black Programme’ and was kept hidden in a secure, remote airfield in Tonopah, Nevada.

Although officially assigned to Nellis AFB, the F-117 pilots and support personnel would leave their families on Monday and fly on contract airlift from Nellis to Tonopah. There we flew only at night in a secret world, returning to Las Vegas typically midday on Friday to spend the weekend with our families.

Our families did not know where we went on Monday and we were not allowed to tell them. (I must confess that my wife was an active duty officer in the air force and she was also assigned to the 4450th Tactical Group). We didn’t want to acknowledge the existence of the stealth fighter to any of our adversaries, so we kept it hidden in the black world.

There were some advantages and disadvantages to ‘deploying’ to Tonopah every week. We were home every weekend, so we couldn’t run into the office or bring work home. So weekend time was truly family time.

However, flying all week at night meant our body clocks were not aligned with our families. It was tough to switch to a daytime schedule on weekends after having flown at night all week. Our ‘dorm’ rooms at Tonopah had room darkening material taped over all our windows so we could not tell whether it was day or night when inside.

We could sleep during the day and work at night. Our medical folks told us that we needed to be in our rooms every morning before sunrise! They felt that our body clocks would be messed up if we were allowed to see the sun rise. Little did they realise that our weekends at home did not include sleeping during the day and never seeing sunrise.

Desert Shield

By the time Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, the 4450th Tactical Group had become the 37th Tactical Fighter Wing. We were immediately told that our squadron, the 415th TFS ‘Nightstalkers’, would be deploying as soon as possible as part of Operation Desert Shield. Although the F-117 had come out of the black world in November 1988, we still were not in any war-planning deployment plans. Therefore, we did not fly out of Tonopah until mid-August and finally landed in Saudi Arabia on August 20, 1990. We first flew from Tonopah to Langley AFB. After getting some sleep, we took off the following afternoon and flew to our staging base in Saudi Arabia.

That flight took more than 14 hours and was the longest sortie I had ever flown. On arrival, we were met by our squadron brethren – they had deployed earlier in order to prepare for the arrival of the stealth fighters.

Unfortunately, they were not able to meet us with beer since General Order One stated no alcohol was allowed in the theatre. We made do with a bottle of water. Now we needed to get down to the business of planning our missions. We had no idea how long we would have before combat would begin.

It turned out we had almost five months to hone our skills and plan our first night missions. We spent the five months flying training sorties in a desert environment that would be similar to Iraq. The picture from our infrared bombing system was not the same as we were used to while flying around Tonopah, Nevada.

We also practised everything without using communication over the radios. This included taxiing to the runway, taking off single-ship and joining as two ships when flying to the tanker orbit in order to air refuel. The only time we talked to other individuals was over the inter-phone with the boom operator while taking fuel off the tanker. Once a week, we would fly with the tanker up to the Iraqi border in order to acclimatise the Iraqis to seeing us flying on the tanker’s wing without actually being in ‘stealth’ mode. On January 16, 1991, things would change.

Combat

On the morning of January 16, I was told to stay in crew rest and not come to the squadron until 1600hrs. Other pilots were told the same thing. We knew something was up and that there was a possibility we would be flying combat sorties later that night.

When we arrived at the squadron, we soon realised we were right. I attended the daily mass briefing with all the other pilots. In this briefing, we were given an intelligence update, weather update and, most importantly, our nightly mission folders that included our route of flight and photos of our targets. Scanning my target folder, I realised that tonight, my targets were in Iraq.

Several hours later, after having said goodbye to my wife, who was also deployed with our unit, I found myself strapped into an ejection seat of an F-117 taxiing to the end of the runway for my first combat sortie since Operation Just Cause [US invasion of Panama].

My heart was beating faster than normal. I made it through the arming procedure at the end of the runway, my wingman and I took the runway to lead the first wave of F-117 sorties into Iraq. Seconds later we were airborne.

We joined into formation and flew to our rendezvous point with the tanker. I topped off with fuel and received a few words of encouragement from the boom operator. Everything was proceeding as planned. After getting my fuel, I settled into my position on the tanker’s left wing and prepared for our 90-minute flight to our drop-off point. My mind was racing.

Before taking off that night, nearly all of us pilots were wary of how well the stealth characteristics of the F-117 would protect us from radars that would direct thousands of Iraqi guns and surface-to-air missiles toward our flight paths. Since the Nighthawk’s targets, including many in downtown Baghdad, were highly defended, wing leaders had privately prepared themselves for F-117 losses as high as 50% on the first night. We didn’t know if stealth was going to work. The engineers all assured us that it would. We trusted them with our lives.

Having arrived at the Iraqi border on the tanker’s wing, I flew into the refuelling position to obtain one last load of fuel. I wanted to have enough fuel to fly into Iraq, hit both my targets, and get back as close as possible to my staging base in Saudi Arabia, in the event I missed my tanker on the way home.

After getting a full load of fuel, things began to happen quickly. I based my departure off the tanker on timing. I had a time-over-target (TOT) of 0251hrs, which was nine minutes before H-Hour, the official start of the conflict. Before I departed the tanker, I put my F-117 into ‘stealth mode’. From now until my return into Saudi Arabia after my target runs, I would be completely communications-out and could not talk or hear anyone else. I was now alone!

Flying the lead F-117 to drop a 2,000lb GBU-27 bomb on to an Intercept Operations Centre (IOC). My objective was to take out the IOC which would control all the Iraqi fighters trying to intercept our non-stealthy coalition aircraft.

Hitting this target meant survival for many of my comrades. I crossed into Iraq and concentrated on flying my planned route to my target area. I identified my initial point (IP) before my target run and performed my bomb-run checklist. My laser was on and my bombs were armed. Every switch was set for a successful delivery.

During the bomb-run I did not look outside of the aircraft. My head was buried in the cockpit. I concentrated on finding my target, a hidden bunker, and delivering my GBU-27. I was 15 seconds from bomb release when I identified my target. My bomb would be the first of the Gulf War. One last thought raced through my mind. Do they really want me to release this weapon and start this war? (I did not realise that Tomahawks had already been launched).

Seconds later, I hit the pickle button and my weapons-bay doors opened, the bomb was released and the doors slammed shut, all within five seconds. I tracked my target for the next 30 seconds and watched my bomb score a direct hit into the bunker. I knew it did not fail when I saw the smoke blow out of the vent ports. The GBU-27 impacted on time, on target, marking the opening of the air campaign.

I started a 180° turn back to the west to fly the 150 miles to my second target, a sector operations centre (SOC).

Now things got hairy. As I turned my fighter back to the west, I looked out over my left shoulder to try to watch my wingman’s bomb strike the same bunker I had just hit. His TOT was one minute after mine. When I looked back, I saw what appeared to be fireworks or some type of explosion filling the sky around me.

At first, I thought the bunker must have exploded, but I soon realised what I was seeing. I was watching the red tracers of the anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and they were all heading towards me. This was the first time I had ever seen AAA. We talked about it during Red Flag training sorties at Nellis, but it was all just talk. This was the real thing.

I snapped my head forward, pushed up the throttles as far as they would go and started a climb out of the heart of the AAA. A couple of minutes later, I realised I had made it out of the target area, but did my wingman as well?

I now had to get to my next target and deliver my second GBU-27. I looked out to the north of my route and saw Baghdad lit up with AAA and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). I thought I was lucky since I was not headed into Baghdad but to the west to hit the SOC. My ease did not last for long.

I looked out to my next target area and over it, too the sky was lit up. I was going to fly into the biggest fireworks demonstration I had ever seen. Because of the delivery system of the F-117 at the time of Desert Storm, I had to be down low to deliver the GBU-27. I couldn’t fly over the AAA, but had to fly into the heart of it. I was not sure I would make it out of the target area without getting hit.

As I approached my second target, I again performed my bomb-arming checks. I identified my target and once more watched my bomb score a direct hit and penetrate the SOC. Coming off the target, I again pushed the throttles as far forward as possible and started a climbing turn back towards Saudi Arabia. Now we would learn the value of the F-117.

As I approached the border of Saudi Arabia, I performed my de-stealth checks and extended my radio antennas. I could now talk and listen to the rest of our aircraft. It was a great feeling to no longer be ‘alone’.

At a designated time, I checked in with my wingman. After several seconds, he answered. Thankfully, he was okay and on his way to rejoin with me at our post-mission tanker. But who would not make it home? Who would have battle damage?

I had a kneeboard on my right leg which included the callsigns and names of all the F-117 pilots flying in the first wave. As I heard them check in, I placed a mark next to their names. After 20 minutes, I looked down and realised I had marked every name. We were all on our way home. The rest of the flight home was uneventful. I flew faster than normal. I was in a hurry to see my wife and congratulate all my fellow pilots.

After landing, every jet was inspected by maintainers for evidence of battle damage. No F-117 had been hit. I was relieved and somewhat happy that I would be spending the next evening in the mission planning cell instead of flying into Iraq.

However, this amazing achievement was repeated the next night. After the fourth night, with no aircraft receiving any battle damage, we all realised that stealth technology really worked. We were all begging to get back up into the air and fly as many missions as we could.

After 1,270-plus Desert Storm sorties, not one F-117 ever received battle damage. Through the remainder of the Iraqi campaign, the F-117 would continue attacking the most difficult targets that required the highest degree of precision. Accounting for only 2.5% of fighter assets, the stealth fighter was credited with destroying a remarkable 31% of targets.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the unsung heroes of the F-117 programme. These were the air force maintainers, who spent countless hours ensuring stealth systems and coatings were kept pristine. They and all the support personnel at our staging base took care of all our living requirements, enabling us to concentrate on planning and flying our missions. My thanks to each and every one of them.

The F-117 programme was remarkable in essentially going from plans to first flight in only 31 months. In addition, it was successfully kept in the black world for a long time. This definitely gave us an advantage over the Iraqi military.

I think the taxpayer got their money’s worth out of the stealth fighter. I was sad to see it retire. However, it’s based on older, 1970s technology, and we possess much better capabilities today. People have asked me, what’s your favourite aircraft? In peacetime, it’s the F-15C – you can dogfight all the time. For combat, it’s the F-117. Once we figured out the stealth technology worked, that was the aircraft for me.