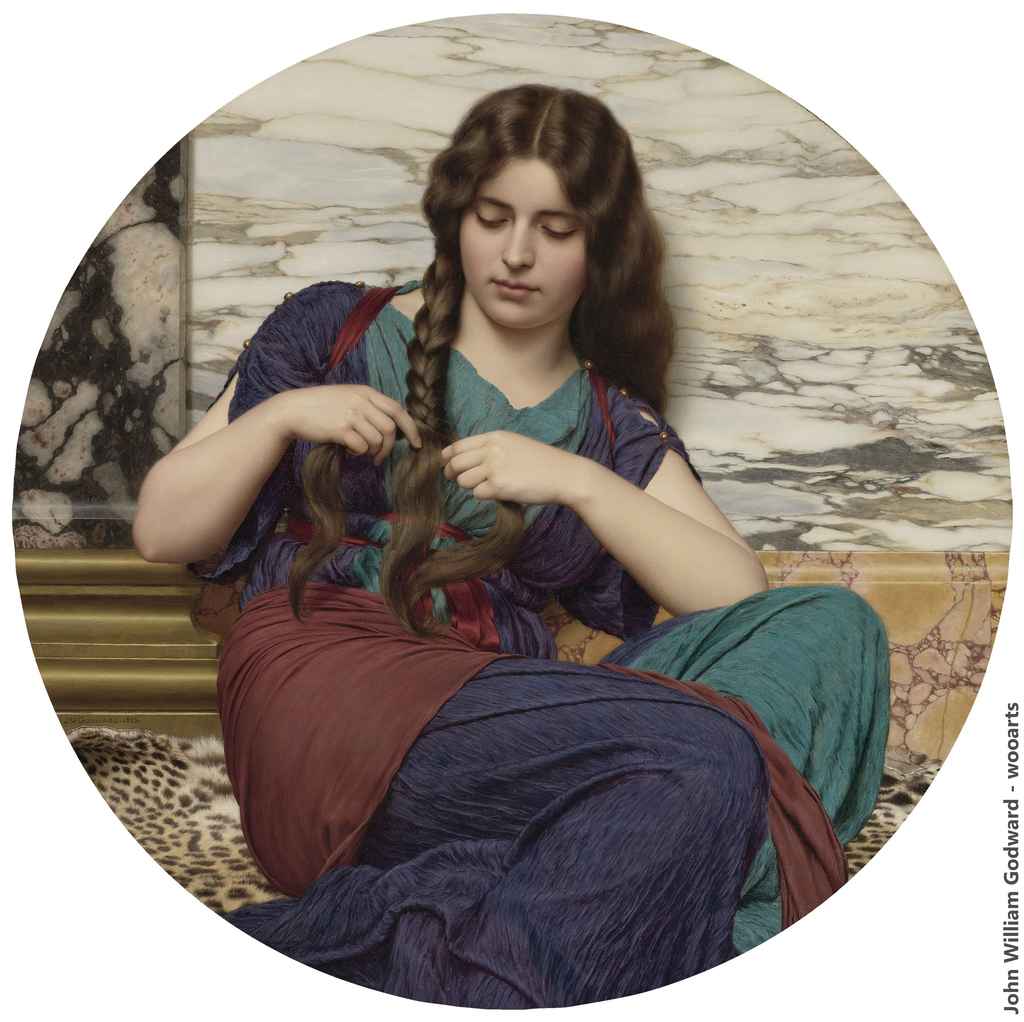

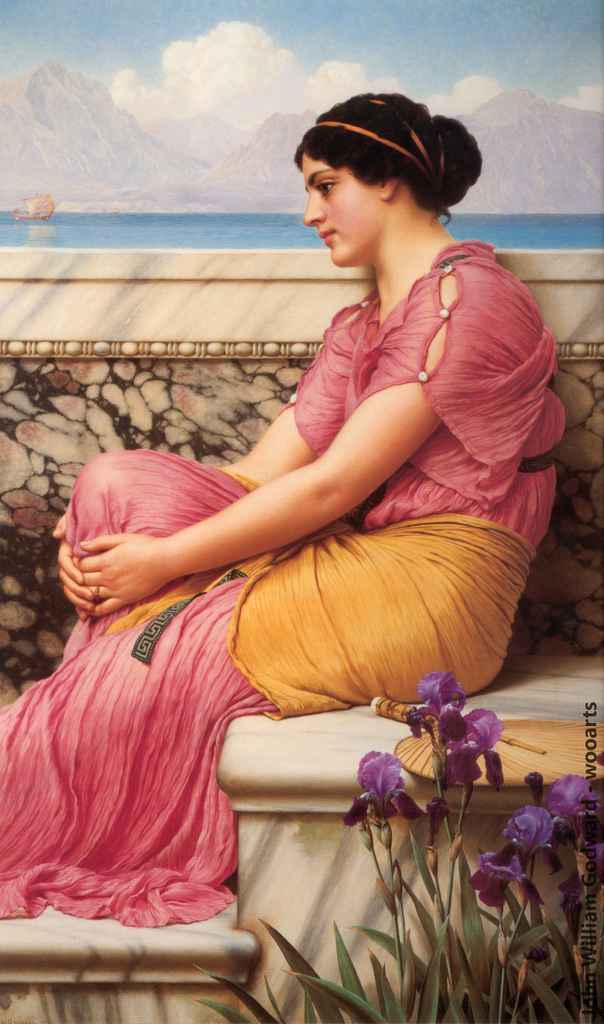

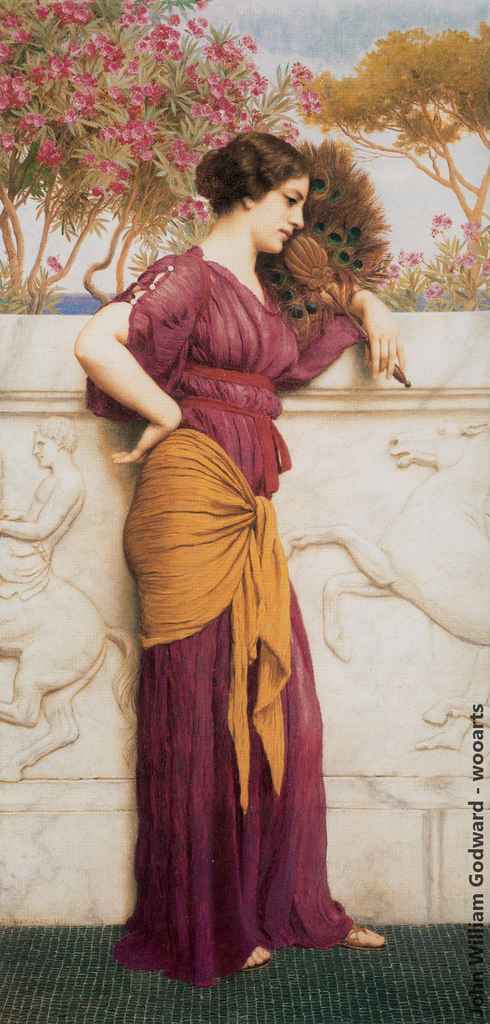

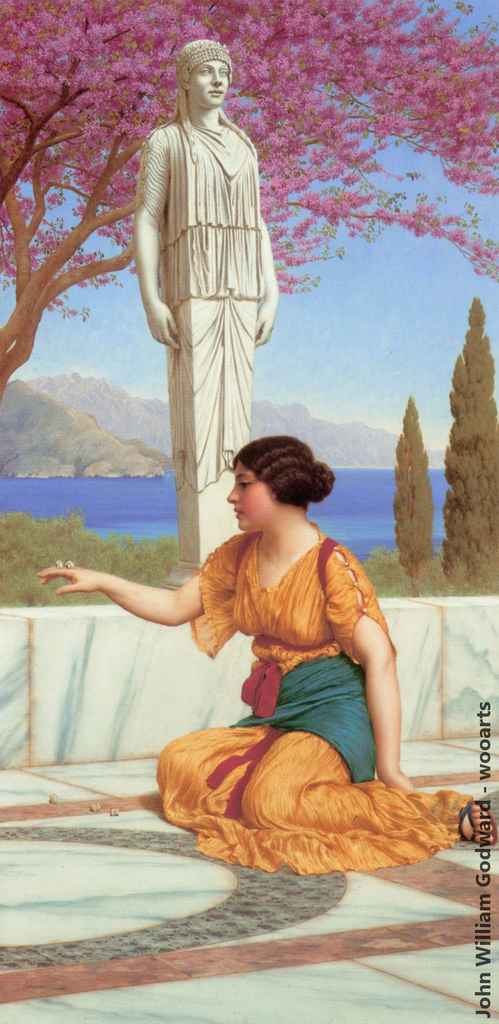

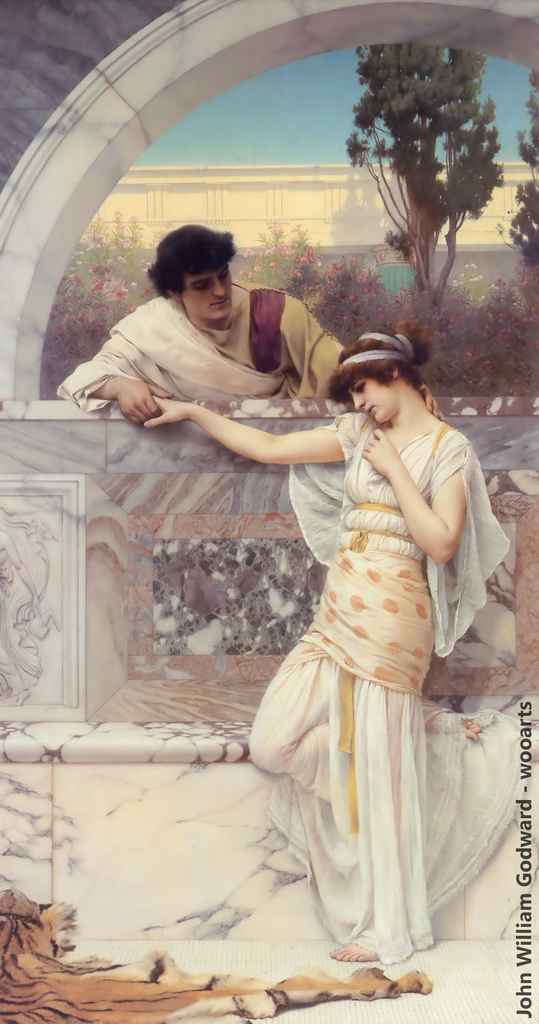

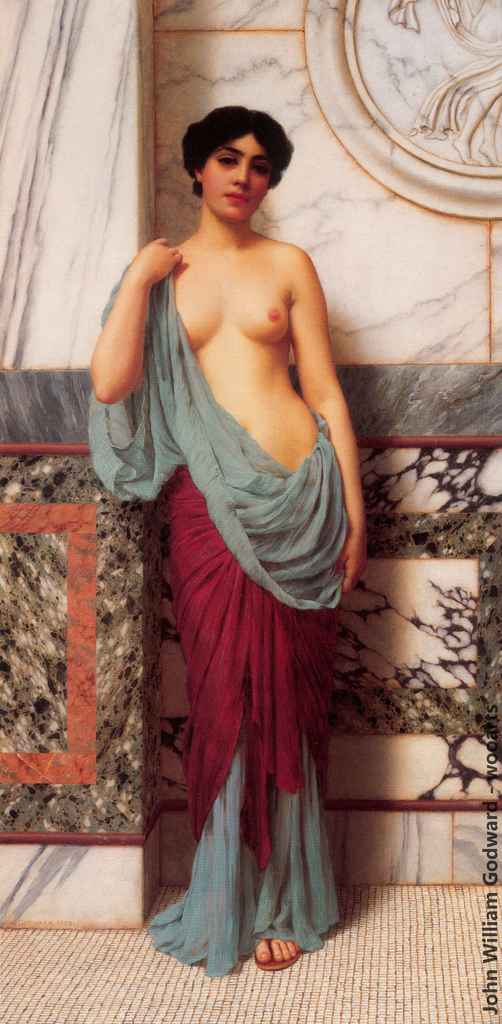

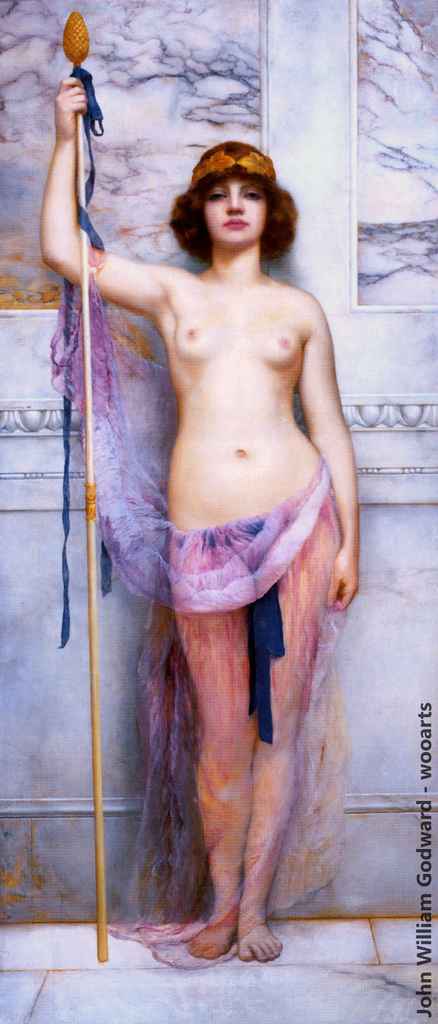

Painting by Artist John William Godward

John William Godward, a painter known for his Pre-Raphaelite and Neo-Classicist style, was born in the Wimbledon district of London, United Kingdom, in 1861. His professional artistic beginnings were somewhat delayed, despite showing an early inclination towards art, as his family largely disapproved of these pursuits. Following his schooling, he worked for a short time at his father’s insurance company, but soon began studying architecture with William Hoff Wonter, whose son, William Clarke, was a painter with whom Godward would become close, lifelong friends. Although there is no definitive documentation, it is widely believed that Godward attended the St. John’s Wood Art School and the Clapham School of Art alongside William Clarke Wonter sometime in the early 1880s.

By the late 1880s, Godward was exhibiting his paintings regularly at the Royal Academy and the Royal Society of British Artists—where he gained membership in 1889. He was also shown by the art dealer Thomas McLean, who championed and produced prints of his work. McLean’s support contributed a great deal to Godward’s growing popularity—and resultantly gave the artist enough financial security to move out from his parent’s home in Wimbledon. He relocated to the Chelsea neighborhood of London, and acquired a lease on a nearby studio that he filled with numerous marble statues and antiques, creating a milieu quite similar to the Greco-Roman settings found throughout his oeuvre.

In 1911, Godward travelled to southern Italy, and ultimately moved to Rome, near the Villa Borghese, where he stayed until 1921. The Villa Borghese, as well as numerous other ancient and classical homes and gardens, provided new source material and appear in a number of his compositions throughout this period of his career. Unfortunately, the artist was plagued by increasingly poor health and depression, and his artistic output drastically declined. The year following his return to London, 1922, Godward took his own life.

Godward’s paintings have been acquired by many premier art collections worldwide, including the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the British Museum, London.

Little has been recorded of the life of John William Godward. Inspired by the painter Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema, Godward imitated his Neoclassical style. Both were counted among the members of the “Marble School,” known for its depictions of subjects drawn from ancient Greek and Roman life placed in elaborate settings, with especially careful and realistic rendering of details like marble and flowers.

Godward regularly exhibited his paintings at the prestigious Royal Academy in London, where they were initially greatly admired by the public. By the time he was in his fifties, however, the Marble School’s approach had fallen out of favor. Godward nonetheless continued to paint in this manner until his death at age sixty-one.

John William Godward (9 August 1861 – 13 December 1922) was an English painter from the end of the Neo-Classicist era. He was a protégé of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, but his style of painting fell out of favor with the rise of modern art.

Early life

Godward was born in 1861 and lived in Wilton Grove, Wimbledon. He was born to Sarah Eboral and John Godward (an investment clerk at the Law Life Assurance Society, London). He was the eldest of five children. He was named after his father John and grandfather William. He was christened at St. Mary’s Church in Battersea on 17 October 1861. The overbearing attitude of his parents made him reclusive and shy later in adulthood.

Career

He exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1887. When he moved to Italy with one of his models in 1912, his family broke off all contact with him and even cut his image from family pictures. Godward returned to England in 1921, died in 1922, and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, West London.

One of his best-known paintings is Dolce far Niente (1904), which was purchased for the collection of Andrew Lloyd Webber in 1995. As in the case of several other paintings, Godward painted more than one version; in this case, an earlier (and less well-known) 1897 version with a further 1906 version.

He committed suicide at the age of 61 and is said to have written in his suicide note that “the world is not big enough for [both] myself and a Picasso”.

His estranged family, who had disapproved of his becoming an artist, were ashamed of his suicide and burned his papers. Only one photograph of Godward is known to survive.

Works

Godward was a Victorian Neo-Classicist, and therefore, in theory, a follower of Frederic Leighton. However, he is more closely allied stylistically to Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, with whom he shared a penchant for the rendering of Classical architecture — in particular, static landscape features constructed from marble.

The vast majority of Godward’s extant images feature women in Classical dress posed against landscape features, although there are some semi-nude and fully nude figures included in his oeuvre, a notable example being In The Tepidarium (1913), a title shared with a controversial Alma-Tadema painting of the same subject that resides in the Lady Lever Art Gallery.[which?] The titles reflect Godward’s source of inspiration: Classical civilization, most notably that of Ancient Rome (again, a subject binding Godward closely to Alma-Tadema artistically).

Given that Classical scholarship was more widespread among the potential audience for his paintings during his lifetime than in the present day, meticulous research of detail was important in order to attain a standing as an artist in this genre. Alma-Tadema was an archaeologist as well as a painter, who attended historical sites and collected artifacts he later used in his paintings: Godward, too, studied such details as architecture and dress, in order to ensure that his works bore the stamp of authenticity.

In addition, Godward painstakingly and meticulously rendered other important features in his paintings, animal skins (the paintings Noon Day Rest (1910) and A Cool Retreat (1910) contains examples of such rendition) and wildflowers (Nerissa (1906) and Summer Flowers (1903) are again examples of this).

The appearance of beautiful women in studied poses in so many of Godward’s canvases causes many newcomers to his works to categorize him mistakenly as being Pre-Raphaelite, particularly as his palette is often a vibrantly colorful one. The choice of subject matter (ancient civilization versus, for example, Arthurian legend) is more properly that of the Victorian Neo-classicist. However, it is appropriate to comment that in common with numerous painters contemporary with him, Godward was a ‘High Victorian Dreamer’, producing beautiful images of a world which, it must be said, was idealized and romanticized, and which in the case of both Godward and Alma-Tadema, came to be criticized as a world-view of ‘Victorians in togas’.

Godward “quickly established a reputation for his paintings of young women in a classical setting and his ability to convey with sensitivity and technical mastery the feel of contrasting textures, flesh, marble, fur and fabrics.” Godward’s penchant for creating works of art set in the classical period probably came from the time period in which he was born. “The last full-scale classical revival in western painting bloomed in England in the 1860s and flowered there for the next three decades.”

Godward and the Death of Greco-Roman Painting

Published Saturday, January 1, 2000

The serene beauty and astonishing technical execution of John William Godward’s paintings contradict the fact that this important artist has received virtually no critical acclaim or art historical recognition. Melancholy, kindly, reclusive, handsome, talented and shy, John William Godward’s life is a mystery, a censored book, self-protected and sealed by his family. Unlike the great Olympian classicists before him, he preferred anonymity and privacy. [By “Olympians” we mean those English classicists who painted at the zenith of classical subject painting, such as Frederick Lord Leighton , Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema , Sir Edward John Poynter and Joseph Albert Moore . This anonymity will end with Dr.Swanson’s biography, aesthetic analysis and catalogue raisonné on the artist, published by Antique Collector’s Club Ltd., available in November of 1997.]

Godward became the climactic figure of English classical subject painting as this genre shriveled under the destructive blaze of the 20th Century avant-garde. He was the best of the last of the great European painters to straightforwardly portray classical Greece and Rome. Herein lies his significance to art history. With him and his colleagues, we see the nightfall of 500 years of classical subject painting in Western art. In Godward’s work we see the final summation of half a millennium of classical antique influence on Western painting. Next to Christianity it was by far the greatest outside influence on European painting. It vanished during Godward’s generation — killed by contemporary nihilistic philosophies.

While pointed references to classicism continued, even unto today, the idealistic rhetoric accompanying it has died. During a period of rapidly declining interest in Greco-Roman antiquity, artists from the 19th Century courageously continued against all odds in this field for the first third of the 20th Century.

Godward was one of the greatest practitioners of the classical ideal. His art represents the summation of this incredibly important paradigm; a microcosm for all classicists during a period aptly called “the twilight of the gods.” It was lost in the hostile environment of the early 20th Century.

This neglect has continued until now, when private collectors have begun to include him in their collections at prices rivaling those of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Art historians are now beginning to reevaluate upward both Godward and his post-Olympian contemporaries.

The reason for this upsurge in appreciation is the realization that the quality of his work compares favorably with other late 19th and early 20th Century painters. Over a remarkably consistent career of almost 40 years, he had created a vital niche for his art.

Since he is often dismissed by biased modernists as an Alma-Tadema clone, a “too late” classicist, a “potboiler” or merely the painter of an insipid world of languorous women on marble benches, no serious study of his art has been undertaken. All of these judgments, in the light of historical distance, can be seen as unjustly prejudiced. And because we are a society that honors “firsts” rather than “lasts,” few art historians have examined the demise of classical-subject painting, of which Godward is the chief exemplar. To date no more than four paragraphs have been published on this artist. This article will rectify that by introducing Godward to a larger audience.

The artist was born into the most boringly respectable family of insurance and bank clerks. Godward’s personal life, by artistic standards, seems equally sedate. The eldest of the five children of John and Sarah Godward, he was born on the 9th of August in 1861 in Battersea on the Thames. During his youth, the family moved across the river to Fulham in Chelsea, and finally to Wimbeldon in Surrey just south of London.

Destined by his authoritarian parents to become an insurance clerk, Godward escaped by taking architectural rendering classes from W.H. Wontner, and perhaps a few night classes from local art schools. Wontner’s son, William Clarke Wontner (1857-1930), a few years older than Godward and further along in his artistic career, also mentored the young man. Later, however, Godward would reciprocate by being a major influence on Wontner’s art.

In 1887 the artist had progressed far enough to exhibit at the Royal Academy. That year he moved from his parents’ house to live and work at the Bolton Studios in Chelsea. There he worked with Thomas Kennington , Henry Ryland , George Lawrence Bullied and others who often painted classical subjects. By 1891 he had his own studio at St.Leonard’s Studio. Then in 1895 he purchased a larger estate at No. 410 Fulham Road.

Godward became a short-lived member of the Royal Institute of British Artists during James McNeill Whistler’s presidency. He participated in exhibitions at the Royal Academy until 1905 and the New Gallery until 1908. He then completely dropped out of English society for the rest of his life. Godward’s family felt that his career was a spot on the family’s reputation. He was sustained in his career by a powerful art dealing firm, Messrs. Thomas McLean of Haymarket Street and by their successors, Messrs. Eugene Cremetti.

Throughout his career, Godward’s paintings typically portrayed beautiful Greek or Roman maidens in diaphanous tunics against a marble background. Often a blue sky and sea, violet mountains, green poplar trees and red oleander or flowering almond blossoms added more color to his already vivid but harmonious paintings.

But as Godward’s art matured, the taste for such works was slowly dying. Already shy and quiet by nature, he became increasingly withdrawn from society as his art fell out of fashion. He traveled to Italy in 1904 and by 1912 moved permanently. The family believed he was lured there by an Italian model he often used in his paintings.

“Running off” with his model shocked the family, who had never really forgiven him for becoming an artist in the first place and for painting nudes in the second.

He could see that modernism had already infiltrated the London art scene and that Rome was more conducive to his work.

Once in Rome he took a studio at the Villa Strohl-Fern near the Gardens of the Villa Borghese. In these exclusive studios he painted many of his finer pictures. The war years were spent in Italy, and he did not return to London until 1920. His health began to fail and his affliction of post-influenza, melancholia, insomnia and dyspepsia got much worse. He returned to his home at No. 410 Fulham Road and moved into the garden studio, since his brother Charles Arthur had been living in the main house. Godward’s art was amazingly consistent and maintained a high technical level throughout his career. Toward the end, however, his poor health had caused him great suffering, his art was reviled and his dealer was about to retire. All these factors led to his suicide in December of 1922. With his burial at the Old Brompton Cemetery at the age of 61 came the precipitous decline of classical antique subject painting. The death knell of the Western European classically antique subject tradition could be heard from many directions. It was sounded in scientific “natural selection,” religious “higher criticism,” economic “international depression,” and in militarism’s “total war.” Most of all its demise came through the challenge of the New Art, which emphasized anti-idealist vocabulary. The idealism of Greco-Roman subject painters of the first third of the century seemed hollow in the face of these onslaughts.

It was the relentless attack of these modernist artistic forces that overwhelmed entrenched classical and academic realism. Godward and other classical-subject artists seemed to wilt under the nihilist fire from the avant-garde and its atavistic assaults. There was also a shift from classical Mediterranean archaeology to more anthropological concerns of non-European tribal societies. These had tremendous influence on modern art and contemporary imagination at the expense of the classical tradition.

The slashing of Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus by a suffragette in 1914 was indicative of the anti-classical sentiments for displaying idealized female form on a “pedestal.” Yet classical-subject tradition seemed to die a few years before, between the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and World War I. Then the last flame of the Greco-Roman classical genre saw its final flicker during the 1920s and ’30s. Rhetorical heritage and education gave way at the same time as an overly conscious attempt was made by its adherents to retain the tradition.

By 1922, the year of Godward’s death, the Bloomsbury School of aesthetic criticism had triumphed over established conservative orders. The Camden Town Group, the London Group and Vorticists, among others, conspired to demolish its conservative opposition. Though oblivious to the finer points of the aesthetic debate, Godward was certainly not immune to its effect. He must have roiled at what he would have considered insane and anti-civilizing art of the post-impressionists and modernists.

Though we have no direct statements from John William, Ivy Godward said that her father-in-law, Alfred, the artist’s brother, felt that Picasso was a lunatic and his art was evil. Alfred was of two opinions about modern art: it was a waste of time and a waste of paint! This likely summed up the feelings of the artist as well, though he was probably more affronted and galled by its ugliness that its incompetence. In the 1930s, Graham Robertson wrote something along the same line: “I have lived for long, happy years … in a lovely land of art and literature where men strove earnestly and I think nobly to create and perpetuate beauty. Now that land has been invaded and overrun by a rabble rout, who have profaned its innermost sanctuaries and polluted them with ugliness and obscenity.”

This indictment is also reflected by Charles Ricketts in March of 1914, after reading a novel by Anatole France: “A sense of fear which is, I believe fairly widespread among thinking men, who dread some sort of decivilising change, latent about us, which expresses itself especially in uncouth sabotage, suffragette(s) and post-Impressionism, cubism and futurist tendencies.”

As a Tadema pupil, John Collier made a remark whose truth would have resounded in Godward as well: “It is impossible to reconcile the art of Alma-Tadema with that of Matisse, Gauguin and Picasso.”

What must have rankled him most were the attacks by modernist brigands upon traditional artistic typologies and prerogatives. At this point in time, many of the conservatives in English art would have been content to have called a truce, but Bloomsbury critics like Roger Fry and Clive Bell smelled victory. Fine art that Godward respected was first marginalized, then repudiated in favor of barbaric and “futurist” aesthetics. Alma-Tadema, who died only a decade earlier, also felt the sting of derogatory criticism. A writer in the January 1913 issue of Nation said, in a review of the memorial exhibition:

Since he is often dismissed by biased modernists as an Alma-Tadema clone, a “too late” classicist, a “potboiler” or merely the painter of an insipid world of languorous women on marble benches, no serious study of his art has been undertaken. All of these judgments, in the light of historical distance, can be seen as unjustly prejudiced. And because we are a society that honors “firsts” rather than “lasts,” few art historians have examined the demise of classical-subject painting, of which Godward is the chief exemplar. To date no more than four paragraphs have been published on this artist. This article will rectify that by introducing Godward to a larger audience.

“I think Tadema himself realized that his greatness was a little dimmed in the eyes of the world before he died. He could sometimes be so bitter that it was clear he heard with apprehension the younger generation of critics and artists knocking at his door.”

The great battle of this period was not between academicism and impressionism, but rather between them and post-impressionism. The general direction of modern art during the first decade of the 20th century was toward breaking down, then negating, the traditional absolutes and values held by the Academy. By the end of his life Godward had seen the rise of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, German expressionism, Russian avant-garde, Italian futurism and worst of all — Dadaism. Godward heartily disapproved of these artistic aggressions.

It is absurd to imagine how Duncan Grant’s voracious abstracts made the meditative work of Godward and his colleagues seem shallow, trite and insipid. The hellfire of modernism burned down the temple of classicism. Interest in significant form, futurism, nonobjective content, abstract design, expressive distortion, flatness, disassociation with the natural world, opposition to the ideals of civilization, and the fiery crucible of the “accident” repudiated classical subject painting.

It is interesting to note that no artist born after the 1860s developed into a major classical subject artist.8 It became nearly impossible for any young artist to pursue this line of painting. Philosophically, it had “hit-the-wall.” No new talent was replenishing the Greco-Roman reservoir, and by the first years of the 20th century it became obvious that it was a dying genre in painting (though not in sculpture). The following list encapsulates all the major painters of the antique in England born during the 1860s.

Solomon J. Solomon (1860-1927)

Cecilia Rea (1860-1935)

John William Godward (1861-1922)

William Reynolds-Stevens (1862-1943)

Norman Prescott-Davies (1862-1915)

Herbert Draper (1863-1920)

Arthur Wardle (1864-1949)

Abbey A. Altson (1864-1949)

Ralph Peacock (1868-1964)

George S. Watson (1869-1933)

The very nature of archaeological subject painting in the new century, which Alma-Tadema helped establish, was inordinately ideal in a crystalline sense. Like Alma-Tadema, Godward helped to demythologize and demoralize the exemplum virtutis from the classical subject. The removal of myth and morality took Greco-Roman classicism two steps closer to its demise. By stripping mythology and portrayal of exemplary deeds from this art, some of the above artists were denying such painting its most potent ally. Inadvertently Godward had contributed to the death of the very tradition he hoped to perpetuate.

Not all classical artists abandoned mythology and morality lessons. John William Waterhouse , for one, saw the power of classical myth as the raison d’etre of his painting. This is why he is considered the best classical subject painter of the late period. Godward’s figures were considered by modernist detractors as peep — show portraits rather than powerful evocations or re — interpretations of Greco-Roman history, morals and legends. This signaled the waning of the classical subject itself. John Ruskin’s Queen of the Air (regarding the modern relevance of Apollo) seems poignant in this context:

It may be easy to prove that the ascent of Apollo in his chariot signifies nothing but the rising of the sun. But what does the sunrise itself signify to us? If only languid return to frivolous amusement, or fruitless labour, it will, indeed, not be easy for us to conceive the power, over a Greek, of the name of Apollo. But if for us also, as for the Greek, the sunrise means daily restoration to the sense of passionate gladness, and of perfect life — if it means the thrilling of new strength through every nerve, the shedding over us of a better peace than the peace of night, in the power of dawn — the purging of evil vision and fear by the baptism of its dew; if the sun itself is an influence, to us also, of spiritual good — and becomes thus in reality, not in imagination, to us also, a spiritual power — we may then soon over-pass the narrow limit of conception which kept that power impersonal, and rise with the Greek to the thought of an angel who rejoiced as a strong man to run his course, whose voice, calling to life and to labour, rang round the earth, and whose going forth was the ends of heaven.

Ruskin’s powerful words seem even more profound against a backdrop of Greco-Roman classicism as “costume” painting. Through trivializing that which had greater power, these painters led, to some extent, to their own marginalization. It is doubtful, however, in the face of radical modernism, that any “return” to the past could have fared well.

Certainly it would have slowed the speedy downfall and softened the resounding crash of the archaeologically based school of art, but it could not have averted it in the least.

A new modernist style of classical painting, made up of artists born primarily in the 1870-’80s, included Ernest Proctor, Harry Morley, Charles Ricketts , Charles Sims , Philip Conard and Braida Stanley — Creek among others. They were able to keep a vestige of classical subject painting going a little longer. They attempted to reinvest classicism with new vigor learned from modernism while retaining myth. However, the classical look of these artists was lost with the demise of art deco, a transitional stylistic phase itself and certainly not a haven for classical subject painting.

Even Pablo Picasso , Ferdinand Leger and Georgio di Chirico had contributed to both the maintenance and demise of objective classicism. On the continent, Picasso, through the formalities of cubism and his later Greco-Roman references, animated “modern classicism.” But all this would have been anathema to the brand of classicism exercised by those high Victorian and Edwardian artists listed above. Godward would have recoiled at their “invasion” of the ancient world.

Though allusions to ancient Greece and Rome were impossible to entirely expunge from the record of 20th century art, it became an increasingly rare occurrence. As modernism had for centuries been the seed which guaranteed the viability of tomorrow’s art, the classical tradition was the soil from which it grew.

Far from being modernism’s nemesis, the classical heritage was the bedrock from which creativity could spring. Now that it was gone, art became a teeming riot, and the avant-garde’s alter ego disappeared. Art as a whole had lost its soul mate, its birshirta.

Instead of an art which measured society, 20th century art became increasingly about its own prerogatives. It became dangerously ingrown. The avant-garde carried on a monologue, whereas classical realism had been a dialogue. Modernism was pour la pour l’art. It became autobiographical rather than societal. High modernism became as esoteric as the purism of high classicism. If antiquity painting told us too much about the past, modernism told us too little about the present. Both were to some extent, elitist. Whereas bourgeois-classicism at least tried to reconcile itself to the masses, modernism came down to only the corporation level.

Now, finally, enclaves of highly talented artists are finding renewal in classical realism. While their numbers have certainly not reached “critical mass” they are growing rapidly. While England is rather behind the curve, America, Spain and Italy are moving along. Allan Banks , Stephen Gjertson , Nelson Shanks , William Whitaker and others have begun to recover the essence of classical ideals and academic painting and picture-making methods. Though none paint with an eye to Greco-Roman subject painting, they have reinvested their art with the classical ideal of Renaissance space. Hilton Kramer spoke of this issue:

What you have to understand is that one of the few constants on the art scene has been an absolutely uninterrupted succession of excellent realist painters. This argument has never died out. It isn’t cyclical, it’s just that people weren’t paying attention.

It is improbable that a Greco-Roman revival will occur except in a formal sense. Whereas in the past the classical-subject was inseparable from formal classicism, it is now thoroughly defined and separated. Formal grounds exist for a revival of abstract classicism but not for antique subject-oriented classicism. Bauhaus and minimalism, perhaps with the vaguest of Greco-Roman reference, may rear itself in post-modernism, but classical subject painting in the bourgeois sense is dead forever among classical realists and mainstream artists.

In reality, classical subject painting was but a veneer for a deeper epistemology which will continue to live in art. It was the gospel of beauty, perfection, tradition and peace that Godward and other artists felt was most profoundly transmitted through the classical subject. In this day of reconciliation between the arts we find that classicism is like the builder’s square to modernism’s mariner’s compass; the past and the future meeting in the present. Both have a lot to learn from one another.