Hello readers and welcome to another “In Search of Our Queer Gardens.” In this edition I’ll be examining the work of the the band the Knife. More music acts? I know! Music must appear to be the only art form I attend to, but there is a reason for why I incorporate so many musicians into this ongoing series, which will be looked into later. I also decided to look at the Knife because they are the first feminist identified band I’ve looked at, and, like with Karen Finley last week, I want to write posts on things I love. No hope for objectivity here, folks!

I was looking at the Knife’s website a few months ago and came across this link in which they compose a playlist of various bands to fit the designated theme titled “Queer Sounds.” I found the idea of Queer Sounds intriguing, particularly in the context of the Knife’s work and one of their more signature aesthetics: the blurring of gender and sexuality in their music. After reviewing some videos and certain songs, I determined that their music incorporated a theme that I will tentatively call “Queering the Voice” — in which expected gender and sexuality norms are subverted and flipped, creating either a narrative (in song, hence the Voice) that is either ambiguous or queer.

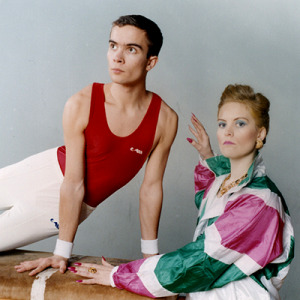

When I thought about it on these terms, I realized that the narratives in their songs alternate between both male and female perspectives in their perspective, crafting a space in which not only gender is in flux but sexuality as well. The Knife mostly does this by altering singer Karin Dreijer Andersson’s voice to sound like a man with fancy recording technology; but not all of the Knife’s gender politics occur from voice modification, as seen the in video for the Knife’s “Pass This On,” which happens to be a good launching point for exploring how these paradigms are subverted.

The subject matter of the song, sans video, is deceivingly simplistic at first. The gender of the singer is presented as female and the song appears to be about a childish infatuation with a friend’s older brother: “I’m in love with your brother / what’s his name / I thought I’d come by to see him again” but becomes overtly more sexual by the end of the song: “does he know what I do / you [sic] pass this on, won’t you?” The three characters in the song are caught in a triangle: the narrator who is in love with the brother and the sibling to whom this secret is revealed and asked to “pass” it “on” to their older brother. By listening to the song only, the attraction between the female sounding narrator and her friend’s brother would appear to be strictly heterosexual but the video flips this assumption on the head.

Instead of the song being a secret “passed” in confidence between two friends, it is instead “performed” in front of an unsuspecting audience (what appears to be a local football league) and the performer is not simply singing the song as way to express her feelings (as in most music videos and musicals ,the narrative or story being told is sung by the storyteller) but is instead lip-synced as part of the performance. The performer also happens to be drag queen, signifying another kind of “performance”, i.e, gender performance, that is happening in the video. Karin Dreijer Andersson, instead of following the formula for music videos, is not the one “singing” the song she literally does sing; she is instead the troubled woman in the back of the room that refuses to stand up and dance. Karin’s brother, Olof, is the young man who the drag queen keeps looking at and eventually begins dancing with her. The two artists position themselves as the siblings in the song’s narrative while the drag queen, whose presence simultaneously constructs and deconstructs gender and sexual norms, publicly announces her love and desire for the brother, winning the approval of all present (in what is an incredibly masculine space) except for the begrudging sister.

While the video is the vehicle for gender and sexuality subversion and not only the song in this case, I think the way the video plays with gender is a excellent visual representation for what the Knife tries to do with gender and sexuality in most of their music, which is to give voice to the ambiguities of gender and also to sexual minorities and non-heterosexual desires. So you might be wondering: “Where is that modified male voice I heard about?” Oh, it is coming and it is about as weird as you may think it is.

I was debating which song should be the introduction for Karin Dreijer Andersson’s male voice, and I settled this one might be the best because of the contrast between her “regular voice” and the male voice that begins at 1:48–

The possible and mysterious allusions to abortion aside, I think that song best demonstrates what the Knife is trying to do by creating two distinct voices, for example, the male voice has an accent that it carries when it is used in other songs, it is, in effect, at alternate identity that spreads the breadth of their work. For the first two years that I listened to the Knife I didn’t know they used a voice modifier so I assumed the male voice was Olof’s (he actually doesn’t sing in the band at all) and I was blown away when I found out that what I had been interpreting as two different people were actually two characters that were voiced by the same person. That male character has very few songs in which he does all the singing, but they are weird little gems:

Handy-Man is exactly what it sounds like: a bizarre, homoerotic dance song. The use of masculine tools as a symbol for failure “I thought you were the Handy-Man” is an interesting reversal. While there isn’t much subterfuge here besides the queer material of the song, its interesting to make note of it within the Knife’s framework of pushing and testing gender and sexual boundaries.

I would argue that the Knife is Queer Art, and this is more based on my my knowledge of more of their work, but I think in the few videos that I’ve sampled my case for their music being distinctly Queer can be made. They are intensely private about their personal lives and we have no way of knowing their sexual identities, but as I tried to reason out with Karen Finley last week, maybe one does not have to be Queer-identified to make Queer art.

As briefly promised in the intro, I said I was going to try to elaborate on why I have used so many musicians. And the various reasons are as follows:

1) This is What I Know: With the advent of iPods, our music is available to us almost whenever. I listen to mine a lot, I know these songs and have had much more personal time to mull over them than I would, say, a poem by Sylvia Plath. I feel comfortable analyzing work that I’m very familiar with.

2) Brevity: A good, dynamic well written song can say a lot in 2-4 minutes. It’s also easier to connect with a song than it may be with some poetry or prose. In our age of multitasking, it is hard to sit on a computer and try to meaningfully engage with a text because some jerk on the internet said you better do it. Which leads me to a more petty point–

3) Accessibility/Ease of Posting: Let’s face it, linking to a youtube video is much easier than quoting multiple passages from a book or trying to elaborate on a scene from a film that cannot be found on youtube. It’s also more engaging for a readership, but it let’s you do the work. If you are not interested enough to watch the videos, great! I’m just pleased I didn’t end up typing out five Sappho poems for you to glance over and not read.

4) For the Hell of It: I can’t write about the music I listen to in an academic setting. Where else can I do it?

Oh, and most importantly, the reason I write about music so often is to pass it on.

1) I LOVE these posts because they’re such a great introduction to bands I think a lot of us wouldn’t know exist (especially this one).

2) I love all of your analysis in this post — the use of two voices, and therefore two characters by Karin Dreijer Andersson, makes the band and their music so complex. I love the genderbending that goes on in their music and music videos in an authentic way. I say authentic because I think that the intent, here, is to make listeners think about gender assumptions, to question our personal views and beliefs, in a way that also enhances the art and makes it powerful politically. Contrasting that to Lady Gaga, who we’re more familiar with here, the self-appointed voice of the queer movement, and her whole problematic publicity stunt with Jo Calderone (I’ve read a lot of criticism about this performance of hers) and her problematic music like Born this Way. (I don’t think that sentence made much sense, sorry).

Like you say, the Knife is clearly queer art, and I also love the argument you presented in this post and your Karen Finley post — that you don’t have to be queer to produce queer art, or have your art read through a queer lens.

LikeLike

Good songs. Lots of Kate Bush and Laurie Anderson behind it all.

LikeLike