Jude Law, 43, gets a little prickly when asked if he ever gets tired of being called charming. It’s the antidote to his smooth exterior, the nose hair plucked. He’s no callow Prince. He’s done Hamlet, for god’s sake. The London-born actor recoils from the noun’s more shallow implications. Seated in an intimate nook in the neo-bordello style Gramercy Hotel Rose Bar beneath a Damien Hirst painting, Law protests, charmingly: “I certainly don’t try to be. But hearing that actually makes me feel a bit, like, ‘Really?’ ”

“It sounds a bit sleazy. A little bit, ‘Oh, he’s so charming.’ ” Though, upon further reflection, Law amends, “I guess it’s better than hearing that everyone thinks I’m an asshole.”

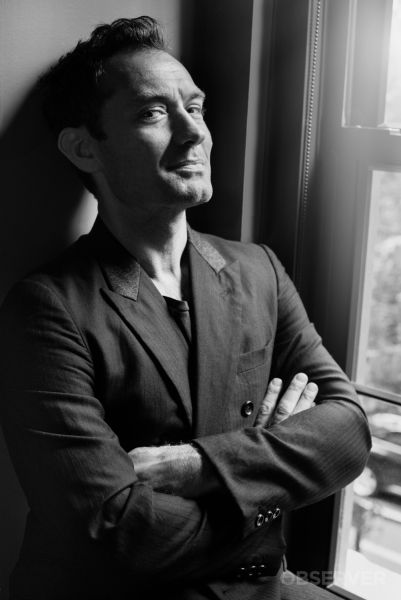

Barring the opinion of a few exes, Law is anything but. He’s the last of the true gentleman, well-dressed in a dark suit, comfortable in his skin and considerate in a way that reflects the good manners instilled by his working mother. His voice soft, with an accent more posh than his South London lineage—his parents were both teachers and orphans who found each other and formed a tight circle of tough but uncritical love around Law and his older sister Natasha, an artist—he eases back into the blue velvet of the banquette and unravels for a bit.

The hard-working father of five joined the National Youth Music Theatre at 15, left school without attending university with his parents’ blessing and took to the stage, where he found early success, accolades and his first Laurence Olivier Award nomination for his role in Jean Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles in the West End at 22 in 1994.

Law simultaneously migrated to films, making strong impressions in Wilde, Gattaca and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil before breaking out big time as the privileged Dickie Greenleaf in Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, for which Law received an Academy Award Nomination for Best Supporting Actor. (He won the BAFTA.) He reunited with Minghella for Cold Mountain and Breaking and Entering; his long list of credits includes playing Dr. Watson opposite Robert Downey Jr. in Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes, Enemy at the Gates, The Holiday and the remake of Alfie, among many others.

Six feet tall, slim but not slight, he is both dashing (recalling Errol Flynn, who he played in The Aviator opposite Leonardo DiCaprio) and self-contained within his unblemished skin. It is not his eyes that capture the gaze—it is those sculpted lips and the words that fall out of them with a surprising openness and curiosity. Minghella, just prior to his passing in 2008 at 54, said of his star, “Jude is a beautiful boy with the mind of a man—a true character actor struggling to get out of a beautiful body.”

Law is quite the character in his latest movie, Michael Grandage’s Genius, which opened Friday. He plays Thomas Wolfe, the larger-than-life North Carolina novelist, author of Look Homeward Angel and other sprawling, passionate autobiographical works of Southern fiction. “Thomas was as big and loud and bold and physical,” said Law. “Some of that bravado and ebullience is his lust for life. He wants to eat and fuck and drink and feel everything so that he can channel it and purge himself of it, almost, you know, vomit into his writing.”

Screenwriter John Logan adapted A. Scott Berg’s meaty, brilliant biography Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, diminishing the roles of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway (played by Guy Pearce and Dominic West) to focus on the fecund and fraught relationship between Wolfe and his Scribner’s editor, Perkins (Colin Firth). The publishing world still considers Perkins the Platonic ideal of the New York editor, even if he never achieved the household name recognition of his authors, which included Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Ring Lardner, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings—and Wolfe.

Law explains the choice to narrow the story’s focus: “John Logan recognized that perhaps as a screenplay, it was more interesting to use and spin webs around the word ‘genius’ and investigate: can genius be shared by two people, by a process, by a collaboration?”

“We overuse the word genius nowadays,” Law continues. “There’s a great line in the film where someone describes Max as being a genius at friendship, which is an interesting idea. I think Thomas Wolfe had an element of genius, but Max added to Thomas’ natural talents.”

There are parallels between the close creative relationship between Wolfe and Perkins and the collaborative nature of filmmaking, which resonates with Law. “You’re given a character on a page, you spin it; you try and fill that character with life and detail, backstory, nuance. Between you and the director, the cast and the crew, you try and create moments of sumptuous truth. The director then goes and sifts through; editors edit and come up with—one hopes—a finessed and more specific, erudite definition of what the piece is about. Genius also looks at a creative process and collaboration.”

The literary adaptation hinges on an intense father-son relationship, one that resonates as Father’s Day approaches, with its celebration of patriarchs, both biological and adopted. “Both men had the background to lead them to a place where they were looking for the surrogate father or the surrogate son,” explains Law. “Max had five daughters, never had the boy he wanted. He found in Thomas his passions for literature and words. In turn, Thomas was born one of many children in a very poor family setup where, as he put it, he had two houses but no home. His father—who was prone to drunken rampages, and would often end up making his mother pregnant, lived in one—and his mother ran a boarding house. He lived between the two, but kind of brought himself up on the streets of Asheville.”

Wolfe’s family didn’t quite know how to handle their intellectual prodigy of a son. “He was always this oddball because he was reading and writing,” Law says of his character. “He finished the library of Asheville by the time he was, like, 12 years old, something like that. He probably felt like he’d never really had a father who understood him, although he loved his father. It’s clear in his writing: Look Homeward Angel and Of Time and the River. But his search was always for the sort of the spiritual father, whom he found in Max.”

While the editor-writer relationship of Perkins and Wolfe evolved into a father-son bond, it also took a more passionate, if not sexual, turn, according to Law. “Not only have they got this father/son thing, it’s almost like this love affair where they abandoned their domestic situations and their other partners for each other; for the love of the word; for the love of the book.” It would not end well: Wolfe left Perkins for another editor and the rejection increased the red-pencil artist’s already athletic martini drinking. Tuberculosis of the brain felled Wolfe at the young age of 37.

Since we’re discussing familial bonds, the discussion naturally turns toward Law’s own five children: Rafferty (19), Iris (15), Rudy (13), Sophia (6) and Ada (1). Back changing diapers for his baby daughter, Law paused to consider his changing relationship to his eldest son. As a parent, letting go is a challenging process—Law concedes he’s not quite there yet. “I’m still in the middle of monitoring Raff’s journey through his teenage years. I’m just aware at the moment that whilst I keep an eye, he wants to lay his own path and do his own thing. I’m trying to give him the space to do that, because of the natural desire to feel one is individual and independent of one’s parents. As a friend said, ‘Letting them fall over and not being there to pick them up…it’s really hard. But they wouldn’t learn to pick themselves up if we didn’t go through that process.’ I’m beginning to see that our role is to guide them into real adulthood for the first time.

“It’s a two-way relationship then, because the kids are going, ‘Help me again.’ And, of course, you’re there to give that help, but they have to ask.” Law leans back on that prom tuxedo blue velvet of the banquette, seeming contemplative and just a little concerned. “At the moment, I don’t feel like Raff’s asking.”

It’s all part of that process of letting go but keeping close, the parenting stations-of-the-cross. When the boy is 12 or 13, a child drops the parent’s hand. Then, perhaps, pulls back on the hugs. “Or,” Law adds, “[they say] drop me around the corner from school. My eldest son has always been a great hugger and a great kisser, actually, which I love, my youngest son, not so much. It’s interesting, isn’t it? How they’re cut from the same cloth, but how individuality finds its expression in different ways. At the moment, with Raff, I’m going through a stage where I’m just aware he needs a huge amount of space. He’s clear that he wants to make mistakes on his own. That’s fine. I’m proud of him for doing that.”

Law continues, the way any parent does when they have the sympathetic ear of shared experience: “It’s interesting talking about it, though. I think it’s always important to keep saying, ‘If you ever need me, if everything goes wrong, if you think you can’t talk to anyone, I’m here. I’m waiting. It’s why I’m here. Phone is on. And whatever you’ve done, whatever’s happened…just let me know.’ You know? It’s important that that hand is there.”

As for his own father, Peter Law, the actor says that while he was very hands-on, he grew up with a lot more hardship. “He had a very colored childhood, which I didn’t really know about until I was in my teens. If I explain a bit about it, you’ll understand why. He was an orphan. He grew up with his grandma who died when he was about 7. He was taken to an orphanage, no money, and was eventually adopted at about the age of 12. Then went from that situation to quite a well-to-do family, sent to a very posh school and suddenly kind of reinvented himself.”

Folding his hands, Law reflects: “I think my father was always aware that he had a tough time, so I always felt like he was quite tough on me in that he was aware that you could have it a lot harder. Looking back, I’m a great advocate for tough love. I always knew I had—in him, and indeed, my mom—boundless love and support and understanding. But there were rules, too. Behaving in the house and civility and helping and limits—we all need limits.”

Comparing his own South London upbringing to that of his children, Law still recognizes similarities—and the recognition of having a vibrant and congenial home to return to. “It’s interesting that my eldest children don’t seem to disappear. Nor did I: I never disappeared. They always want to come home, which I think is a really good sign. In the end, home’s comfortable, it’s safe and it’s interesting, I hope. They think, ‘Oh, well, maybe [our parents are] older than us, but they’ve got interesting people gathered round.’ I always felt like that in my house. It felt like there was stuff going on that I wanted to be a part of.”

Also, like Wolfe and Perkins, Law has a major father figure in his career, the late Minghella, whose premature death left a long shadow over his family and many collaborators. “He was very much [a father figure]. Funny enough, he was introduced into my life originally by my mom, who directed a play of his and went and met with him. So I remember his name in my life years before I actually worked with him. As an actor, he was a wonderful teacher and a great example, and it wasn’t just a sense of comfort in the relationship we forged as actor/director, it was also, he had a wonderful, healthy, positive desire to run a happy set and to encourage his leading actors to embrace and, if you like, be the ‘hosts of the party’ as he would put it.”

On the set of Cold Mountain, which was shot in Romania, Law reminsces, Minghella came and got his lead actor at the end of a “really tough day’s shoot,” and they went around visiting the local extras playing soldiers slogging through the muck and mud. Together, they went around dispensing “ciggies and chocolate,” giving thanks. “It was a process of collaboration,” concludes Law with a rueful chuckle, “even if we all ended up doing what he wanted to.”

Since then, Law has worked with Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, Nancy Meyers and Steven Soderbergh, Wes Anderson and Guy Ritchie. Of the director who cast him as the honorable Dr. Watson in the most athletic version of the Holmes saga, Law says: “Guy’s embraced sort of the big-budget movies. You know, he has no apology whatsoever to the fact that he enjoys making big movies with big budgets and lots of people. Now, some people do. Some people are intimidated by that. Some people don’t necessarily have the swagger to pull that off. He eats that stuff for breakfast.”

As the once quiet bar begins to pick up, and the sound of billiard balls clacking on the felt nearby provides percussion, Law returns to the topic of fathers and sons, and how these relationships shift over time. “It’s in an interesting stage now. My dad is in his 70s, and certainly, in no way frail, but in a new chapter of his life. For me, in my 40s, there’s a sort of inbuilt, in my mind, desire to step up and be the sort of paternal figurehead of the family and make sure that he’s all right and Mom’s all right. That natural, almost relay of responsibilities and experiences, is a wonderful shift, too, in the family makeup.”

Allowing for a long pause, and a cross of his legs, Law continues: “Because my parents were both orphans, this is new for our family. Being grandparents is extraordinary, because they never had grandparents, and I didn’t really have grandparents. I had an erratic kind of relationship with my father’s [adoptive] parents who were much older and died when I was quite young. So the Law family is really just kind of inventing itself now. It starts with my parents. It’s all new stuff.”

Standing up with a stretch, Law takes one last long look around, up at Hirst’s Cytosine-5-H that hangs above our plush seats. Then he looks down and says, “I think I’ll go write a letter to my son.” As he strolls away, across the bordello bar at the tony hotel in his sharp black suit, his left pant leg hikes just a bit, revealing a vulnerable few inches of skin. ν