Source: Rafael Medoff, The Daily Beast, January 26, 2016

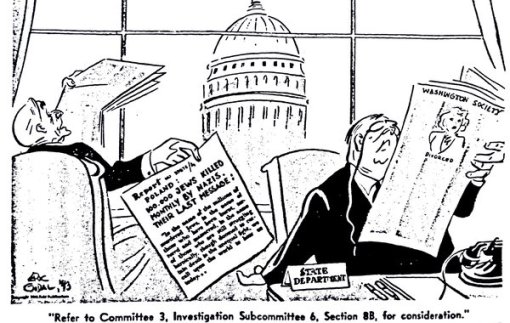

Just in time for International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Iranian government has announced that it will be holding another “Holocaust Cartoons Contest,” in which the cartoonist who most viciously mocks the Nazi genocide will be awarded $50,000. It may be tempting to dismiss such Iranian mischief as harmless foolishness, but Tehran’s hateful contest reminds us that political cartoons increasingly are recognized as powerful instruments of influence.

A cartoon in the New York World played a crucial role in the outcome of the 1884 U.S. presidential race: The Democrats plastered Walt McDougall’s send-up of Republican candidate James Blaine on thousands of billboards across the state, helping to deliver hotly contested New York to Democrat Grover Cleveland (he won the state by just 1,100 votes). In the early 1900s, politicians in several states were so stung by cartoonists’ barbs that they introduced legislation to limit what cartoonists were allowed to draw; in Pennsylvania, for example, the governor initiated a bill to stop cartoonists from portraying elected officials as birds or other animals.

In the 1930s, the Hitler regime used cartoons to incite hatred of Germany’s Jews. The leading Nazi propaganda organ, the weekly newspaper Der Sturmer, was filled with vicious caricatures of Jews as vampires, insects, and especially as sexual defilers of German women. A typical cartoon would feature a huge, leering spider with a Jewish face attempting to ensnare an innocent German maiden, or a swarthy Jewish doctor hovering over a sedated, half-dressed female German patient.

Israel’s Foreign Ministry recently released a brief YouTube video comparing the anti-Jewish stereotypes in some contemporary Palestinian cartoons to the images used by Hitler. While one should always be cautious about making comparisons to the Nazis, it certainly was disturbing to see a recent cartoon on a Palestinian Authority website showing a leering, hook-nosed Israeli soldier, beginning to disrobe while pinning down a weeping Muslim woman wearing a headdress representing Jerusalem’s most famous mosque. The caption read: “Al Aqsa is Being Raped.”

Israeli officials contend that the recent wave of Palestinian stabbings and car-ramming attacks has been inspired in part by Palestinian political cartoons portraying such violence as heroic and encouraging young Palestinians to use knives and automobiles as weapons.

The best-known examples of the link between cartoons and violence are not the cartoons urging readers to take up arms, but rather the cartoons that were met by violent Muslim protests. These include the riots following the 2006 publication by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten of cartoons depicting Muhammad; the 2015 massacre of the staff of the French weekly Charlie Hebdo, which had published Muhammad cartoons; and last year’s terrorist attack on a Texas event that was showcasing caricatures of Muhammad.

Such violence has had a chilling effect in some quarters. The editors at Yale University Press in 2009 removed all the Muhammad cartoon images from a book they published about the cartoon controversy. Several prominent cartoonists, including Garry Trudeau (“Doonesbury”) have asserted that Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons about Muhammad were the equivalent of “hate speech.”

But even if that characterization were accurate, the fact is that in America, hate speech is legal. The possibility that someone’s words may offend is no reason to muzzle the speaker. The right to offend is part of the right to free speech. And frankly, offending people is practically the raison d’être of political cartoonists.

That does not mean that every political cartoon deserves the Housekeeping Seal of Approval. It means that it is up to editors to decide if a cartoon is so tasteless that it should not be published. And it is up to readers to decide if they dislike a particular cartoonist so much that they do not want to purchase that newspaper.

Of course there are different reasons people may take offense at a cartoon. Many people were troubled recently when a cartoon in The Washington Post depicted the young children of U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz as trained monkeys; there is a general consensus in the political world that candidates’ children should be off-limits. The Post apologized and pulled the cartoon.

But sometimes cartoons that at first glance appear to be tasteless, may not actually be. Charlie Hebdo last week published a cartoon that many interpreted as suggesting that the drowned Syrian refugee boy, had he lived, would have grown up to sexually harass women. Some pundits, however, understood that cartoon to be mocking opponents of Muslim refugee immigration—similar in spirit to the famous 2008 New Yorker cover depicting Barack Obama as a Muslim and Michelle Obama as an armed revolutionary. That cartoon was intended as a comment on how some of the Obamas’ opponents perceived them.

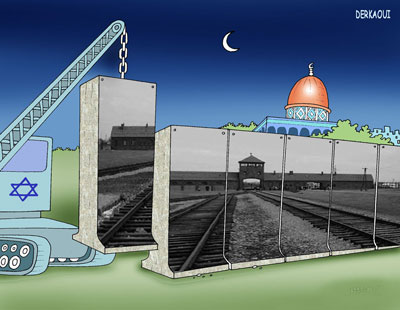

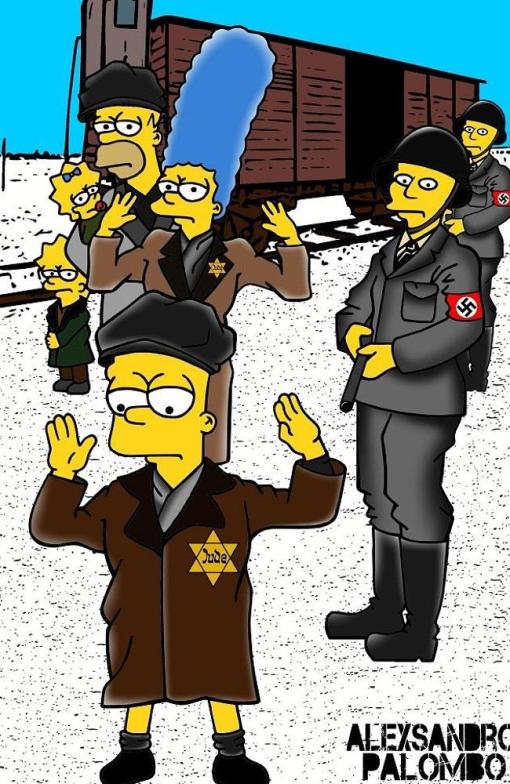

The vigorous reaction and debate over such cartoons is precisely what one would expect in a free society. In Iran, by contrast, the only kind of political cartoons that can be published without the cartoonist being imprisoned are those which the regime approves—for example, cartoons denying the Holocaust or comparing Israel to Nazi Germany. Here in America, we ensure cartoonists’ freedom to skewer hypocritical politicians or antagonize interest groups by guaranteeing their right to irritate or offend. And if they cross the line into the realm of tastelessness, then the natural forces of reason and taste usually serve as a counter.

This informal system of checks and balances has served cartoonists, editors, and the public well since our country’s earliest days. No doubt totalitarian regimes will continue to use cartoons to advance their aims, because they know that cartoons are powerful instruments of persuasion. But for that same reason, free societies must continue protecting the right of cartoonists to compete, unrestrained, in the marketplace of ideas.