by Piter Kehoma Boll

Last week I presented the lovely five-slotted sand dollar, a very common echinoderm along the Atlantic Coast of the Americas. But as we all know, species rarely live by themselves. All kinds of association exist between organism, and today our species is one that lives closely associated with the five-slotted sand dollar, the sand-dollar pea crab, Dissodactylus mellitae.

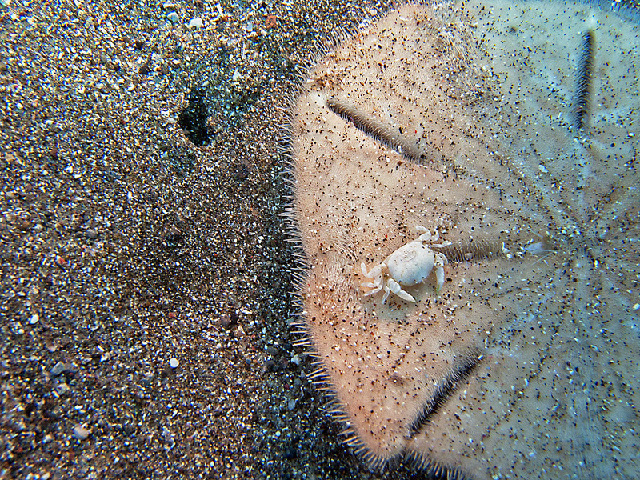

The sand-dollar pea crab is, like its name suggests, a crab. A very very small crab indeed. Adult males reach up to 3.5 mm in size and females do not grow larger than 4.5 mm. They have a light-yellow to white color, sometimes with a complex pattern of darker marks on the dorsum.

The natural habitat of the sand-dollar pea crab is the surface of sand dollars, especially the five-slotted sand dollar. As they are very small, they live very comfortably among the hairs and spines of their host, most commonly on their ventral side, protected from light and possible predators.

For some time it was unknown whether the relationship between both species was that of commensalism, where the crab only eats together with the sand dollar, or of parasitism, where the crabs steals food from the sand dollar or feeds on the sand dollar itself. Analysis of the stomach content of the crabs revealed that up to 80% of its diet consists of tissues of the sand dollar, so that their relationship is most likely parasitic. In fact, it has been shown that the presence of the crabs reduces the number of eggs that female sand dollars produce.

The maximum number of crabs observed on a single sand dollar was 10, but this number is highly dependent on the crab’s life stage. In summer, juveniles often prefer to live together, sharing the same host, but as they grow they disperse and prefer a solitary life, not sharing their host with others of the same species. When they are sexually mature, though, they often share the host with another crab of the opposite sex, thus facilitating reproduction. However, males seem to be much more common in the population, so males pairing with other males are more common than males pairing with females.

Reproduction seems to occur around late summer and fall along the coast of North America, after which the number of adult crabs starts to decrease. Juveniles start to appear in late spring, eagerly looking for sand dollars to colonize.

In the sea, different species associate even more frequently than on land. And we know that wherever there is life, there will be another life to parasitize it.

– – –

– – –

References:

George, S. B., & Boone, S. (2003). The ectosymbiont crab Dissodactylus mellitae–sand dollar Mellita isometra relationship. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 294(2), 235-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(03)00271-5

Telford, M. (1982). Echinoderm spine structure, feeding and host relationships of four species of Dissodactylus (Brachyura: Pinnotheridae). Bulletin of Marine Science, 32(2), 584-594. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/umrsmas/bullmar/1982/00000032/00000002/art00017

– – –

* This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.